Debating in the Upper Ohio Valley during the early 20th Century

By Bruce E. Daugherty

Religious debates are rare today, but this has not always been the case. Forensic controversy has long been a part of the legacy of the Restoration Movement. In Bill Humble’s study of Alexander Campbell’s debates, he pointed to the younger Campbell as having restored debate as a means of advancing truth. He concluded, “The Restoration Movement was born in controversy, flourished as supporter and critic discussed its relative merits, and was molded in the flaming crucible of public debate.”[1] An online site has a compilation of more than 9000 debates in the Stone-Campbell heritage, more than 8500 of which occurred in the 20th century.[2] In a survey whose results were published in 1966 James Swinney found 112 preachers in churches of Christ had conducted approximately 1108 debates.[3] Swinney estimated this represented one-quarter of all debates conducted by representatives of churches of Christ in the first sixty years of the 20th century. West provided this summary of debating in the period:

Clearly then, the debates of the first half of the twentieth century were generally exciting and popular ways of getting the primitive gospel across to audiences. While some discussions lacked in dignity, highlighted rudeness, and portrayed a biasness that seemed to say that the truth was not really the goal of the participants, this was generally not the case. Debaters among the churches of Christ were numerous, confident, and generally effective.[4]

What good resulted from the numerous debates of an earlier era? Swinney’s survey suggests that the value of debates was mixed. Debates, as a form of mass media, were judged as yielding the best results in generating awareness and interest on various subjects but ineffective in changing positions previously held.[5] Haymes believed that results were dubious as fierce discussion was waged over “minute distinctions.”[6] Casey argued that “the divisive nature of debate with its implicit argumentative image of ‘war’ and ‘combat’ relegated the quest for truth to a secondary position.”[7] In contrast to the above, Highers stated that debating “. . . proved to be one of the most effective means of communicating the gospel and reaching those outside of Christ.”[8]

The Upper Ohio Valley was the scene of several debates held in the first half of the 20th century by preachers who sought to defend and advance the cause of New Testament Christianity. To what extent did debating help accomplish this task? To what degree did they reflect the conclusions of Swinney, Haymes, Casey, and Highers? Did any good result from these debates? This article will seek to answer these questions by surveying the legacy of debate in the Ohio Valley that furnished a rationale for justifying their usage in the twentieth century. Then investigation will be made of two debates that took place in the Upper Ohio Valley and their lasting influence.

Legacy of Stone and Campbell

The Upper Ohio Valley had played host to religious controversy since the days of Barton W. Stone and Alexander Campbell. The plea for a union of Christians on the basis of a return to the New Testament led to challenges to debate by denominational leaders in the 19th century.

Following the publication of the Last Will and Testament of the Springfield Presbytery, Barton Stone found himself engaged in controversy as he made his way out of denominational thinking. Stone, a man of a gentle and pious spirit, would not participate in debates. Despite the fact that his temperament was not suited for forensics, Stone still engaged in religious controversy through his writings. Looking back at his life accomplishments, he wrote:

One thing astounded us; the clergy of all the sects, who should be foremost in every good work, were our bitterest opposers. We had to combat for every inch of ground we possessed and for every fortress we gained.[9]

Stone went on to speak of the “warfare” he had conducted for half a century. Modern day assessments of Stone as too pious to debate, need to note Stone’s description of his ministry in militaristic terms for a more balanced view of his life.

Thomas Campbell, having already experienced bitter religious strife in Ireland and Scotland, believed “no practical good” could result from debating. His son Alexander initially agreed with his father’s views, but became persuaded that controversy was inevitable and that debate could be a legitimate means for the advancement of truth and the overthrow of ignorance and error. Promotion of the agenda contained in his father’s Declaration and Address led to defending its principles. Campbell wrote: “The ground occupied in this resolution afforded ample documents of debate. Every inch of it was debated, argued, canvassed for several years, in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Ohio.”[10] In 1820, Alexander Campbell met Presbyterian John Walker at Mt. Pleasant in Jefferson County, Ohio across the river from Campbell’s home in Bethany, Virginia. The debate on infant baptism also permitted Campbell to diffuse his views on a return to primitive Christianity. The notoriety Campbell gained following the debate, convinced him that “. . . public discussion, conducted with moderation and good temper, is of all means the best adapted to elicit inquiry and exhibit truth . . .”.[11] Campbell’s educational opportunities, as well as his rational and logical manner of presentation, permitted him to be well prepared for the task.

All of Campbell’s major debates took place in the Ohio Valley. In 1823 he defended the purpose of baptism as he met Presbyterian W. L. MacCalla at Washington, Kentucky. Cincinnati was the site for his debates with the skeptic Robert Owen in 1829 and with Roman Catholic bishop John Purcell in 1827. Campbell’s last major debate was held in Lexington, Kentucky in 1843 as he challenged Presbyterian preacher N. L. Rice.

In participating in these debates, Campbell believed he stood in good company. He wrote:

No man every achieved any good to mankind who did not wrest it with violence through the ranks of opponents-who did not fight for it with courage and perseverance, and who did not in the conflict, sacrifice either his good name or his life. John, the harbinger of the Messiah, lost his head. The Apostles were slaughtered. The Savior was crucified. The ancient confessors were slain. The reformers all have been excommunicated.[12]

Rationale for Debating

The popular perception of the debater is of a pugnacious individual itching for a fight. But in the early 20th century, public preaching of the gospel elicited challenges to debate. It was not unusual for a gospel meeting to be interrupted by someone from the audience and the preacher to be challenged to debate on the spot. Effective gospel preachers in the period were often required to be effective debaters as well. Many debates resulted from challenges to a speaker’s message.

J. W. Shepherd, one time office manager of the Gospel Advocate and a co-editor of The Christian Leader for many years, was a seasoned preacher and debater. Shepherd was a participant in numerous debates, most often serving as moderator for others. His friend and fellow preacher, I. B. Bradley testified to Shepherd’s valuable forensic assistance:

He is the best moderator I have ever seen, being perfectly acquainted with the rules governing controversy and thoroughly conscientious and honorable in his treatment of the disputants. He stands for honorable and decent controversy, stripped of all frivolity and levity, and urges the issues to be treated upon their worth and the speeches to be dealt with as to their merit.[13]

No one tested Shepherd’s belief in honorable controversy more than R. H. Pigue, a Methodist preacher and debater. Pigue, who held many debates in the Mississippi Valley, had gained his reputation by “sarcasm, ridicule, misrepresentation, and bull-dozing.” For Shepherd, debates with opponents like Pigue were destined to end in “mud-slinging” and he advised his fellow preachers to accept challenges to debate but with opponents who would be honor bound to abide by the rules.[14]

West Virginia native A. A. Bunner was often challenged to debate during his preaching. Bunner became an experienced oral debater through these challenges. In Bunner’s only written debate, his opening address to a packed auditorium in the Marion county (West Virginia) court house spoke of his view of the value of debating:

I am aware of one thing, that is that there are people who are opposed to these discussions; many excellent people are opposed to them, because they think they do not do any good. For my part, I think a religious discussion, when conducted in a proper spirit, is calculated to do more good, than simply preaching to the people. If I stand before you in defense of the truth, I, of course, in a discussion of this kind, get more people to hear me than I would on ordinary occasions. If I have the truth, it enables me to get the truth to more people in an investigation of this kind than on ordinary occasions . . .[15]

Hoosier native Thad Hutson spent many years preaching in the Ohio Valley. Hutson held debates in seven states and had earned a reputation for being “severe.” Hutson did not believe that Spirit of Christ excluded debating and confrontational preaching. He declared:

. . . what becomes of this shilly-shally, namby-pamby, milk and water, sugar and cream kind of preaching that is afraid to say devil or hell in the pulpit; that avoids the unpleasant duty of exposing sin, both in theory and in practice, lest some would boycott him or withhold their support or cry out, ‘He ought to show the Spirit of Christ’.”[16]

The widow of Ulysses G. Wilkinson, an evangelist from Oklahoma who had conducted over 150 debates, shared a rationale for debating with the readers of the Christian Leader. She believed debating was sanctioned by God. This authority came from Isaiah 1:18 where God through the prophet declared, “Come let us reason together.” Mrs. Wilkinson recognized that to teach any subject, religious or secular, included being prepared to answer those who would contradict what was taught. Mrs. Wilkinson believed that debating was better than fighting straw men.

The anti-debater believes in doing both sides of the debating, for then he can have it his own way. The debater believes it fair to let his opponent represent his own side of the question.[17]

Mrs. Wilkinson went on to cite examples of God’ servants who stood firmly for truth and defended it in the face of opposition: Moses in the court of Pharaoh; Elijah and the prophets of Baal at Mt. Carmel; Jesus’ encounters with the scribes, lawyers, and Pharisees; Paul with the philosophers on Mars’ Hill. She believed that this was what Jesus meant when He said, “I come not to bring peace on earth but a sword,” (Matt. 10:34). Armed with this type of rationale and following the examples of debating in earlier generations, the preachers of the Ohio Valley entered the forensic arena.

Memorable Ohio Valley Debates

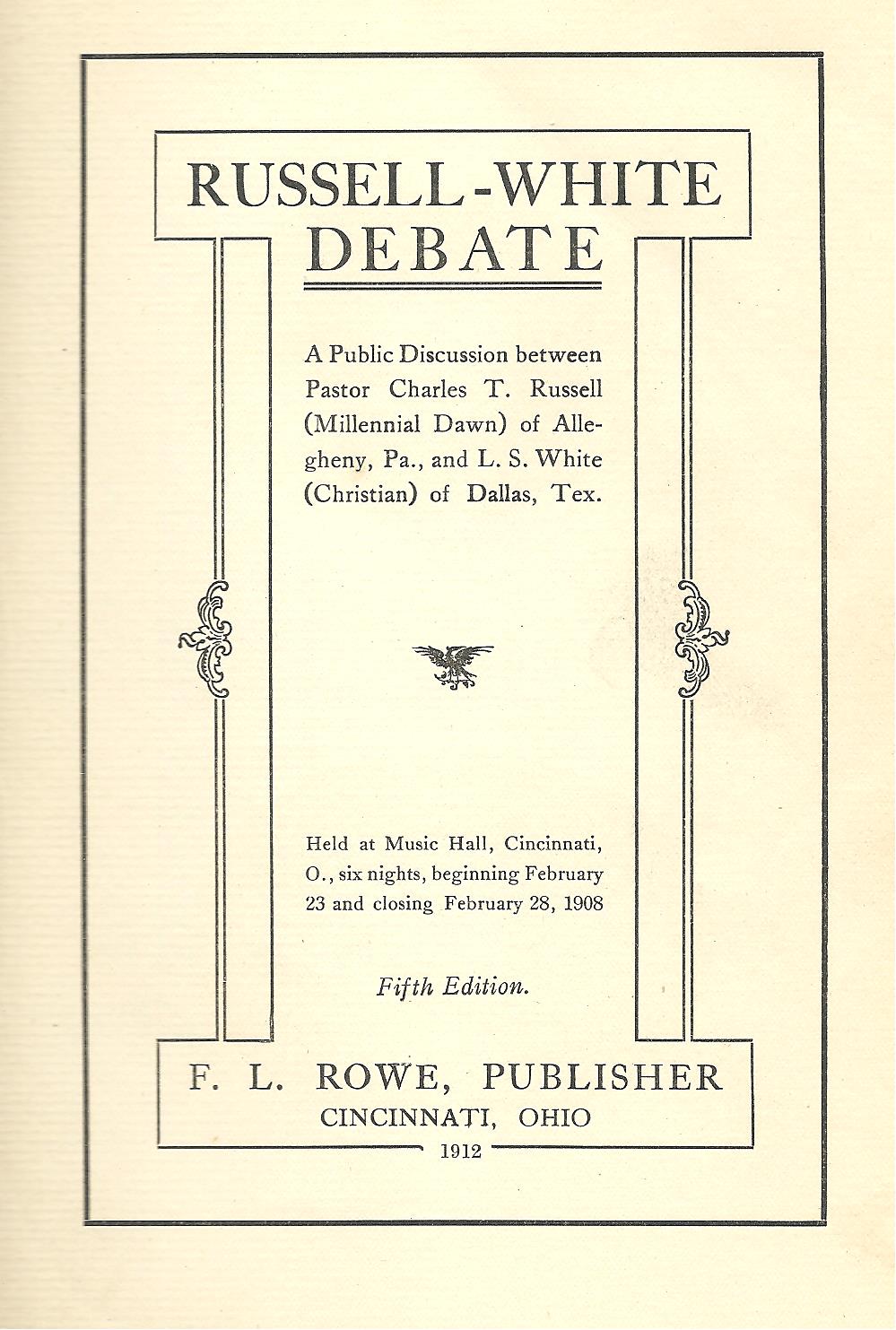

The Russell-White debate (Oral and Written, February 1908). Charles T. Russell of Allegheny, Pennsylvania, founder of the Millennial Dawn students (forerunners of the Jehovah’s Witnesses), met L. S. White of Dallas, Texas to discuss the nature of the kingdom of God. This debate was held in the Music Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio. It generated widespread public interest and was published by Fred Rowe, owner of the Christian Leader and the Way.[18] In addition to Rowe’s publication which was recorded by a stenographer, the debate was carried in the Cincinnati Enquirer, a large local paper. The proposal for debate had been initiated by A. A. Bunner. Bunner was an experienced preacher and oral debater, but at this time he had not participated in a written debate. He felt more confident trusting someone else to meet Russell. After eight months of correspondence between Rowe and Russell, the debate was arranged. L. S. White had been selected on the recommendation of M. C. Kurfees and R. H. Boll. The young preacher from Dallas had already conducted 17 debates. The debate was held on six nights beginning February 23rd and ending February 28th. In addition to discussion on the kingdom, related topics addressed were the possibility of repentance and salvation after death, the state of the dead, punishment of the wicked, the Millennium, the second coming of Christ, and baptism for the remission of sins.

Arrangements for the propositions had taken two months’ correspondence between Russell and White. Russell insisted that there be no moderators for the speakers, but allowed a different chairman to oversee each night’s speeches. Russell also refused to follow any rules governing the conduct of the debate. White complied with these conditions realizing the debate would never have materialized without them.

The lack of adherence to standard debate procedures allowed Russell to read from already prepared speeches, which included his replies to White’s arguments! As one observer put it, “Mr. Russell’s speeches were practically cast in mold before delivered and his auditors were impressed with the fact that he possessed very little impromptu ability.”[19] To read the debate is to be reminded of political debate in this era. Rather than debate the propositions and answer the arguments, each speech resembles a thirty minute infomercial for the candidate. Typical of this procedure were the first speeches of both men on Tuesday evening, the third night of the debate. White went first, affirming the proposition for the evening, “The Scriptures clearly teach that the punishment of the (finally incorrigible) wicked will consist of conscious, painful, suffering, eternal in duration.” White defined his terms. He then called attention to the Bible terms for the unseen world of the dead – “sheol” in the Old Testament and “hades” in the New. White pointed out that neither of these terms indicated punishment of the wicked in the afterlife though they had often been translated as “hell” in English versions of the Bible. White then brought up the Bible word “gehenna,” uniformly translated as “hell” in the Authorized Version and the twelve passages in the New Testament where it occurs. In addition, White supported his case by citing verses speaking of eternal reward and punishment. White then offered Russell a copy of 18 questions on the proposition and stating, “if he does not answer them then you can know that he can not do it.”[20]

After some preliminary remarks addressing how the debate was being reported in the local paper, Russell began his reply negating the proposition. He declared that he once believed the proposition. As a young man he had admired Spurgeon’s sermons on hell. But he had come to the conclusion that “this terrible doctrine has sent many to the madhouse. I do not wonder that others seek to drown the thought of it in pleasure, in business or in the intoxicating cup.”[21] Russell then denied that his doctrine of annihilation of the wicked had a bad influence on humanity. He related a story of how his teaching had helped a man from Mississippi to leave his wicked life. He then offered other testimony of how his Tract Society had led others to God and away from a life of crime. As proof of his claim he asked that if there any in the audience who were fully consecrated to God through Russell’s teachings, would they stand. About one hundred people stood up. He then called out that if there were any in the audience who had been fully consecrated to God by the doctrine of eternal torment to stand. Two people stood. Russell stated, “Eternal torment is claimed to have converted two, and the gospel of the love of God, the justice of God, has brought over one hundred into harmony.”[22] Russell refused to respond to White’s citation of scripture saying that they were texts which have been misinterpreted since the Dark Ages. He said Protestants borrowed the doctrine of eternal punishment from Roman Catholicism, rejecting its only palatable feature, purgatory. Russell injected his rationalism into the argument as he conjectured as to the inconsistency of how a literal drop of water could be given to a spirit being as in the story of the rich man and Lazarus. He then closed his speech by a discussion of the etymology of the English word “hell” and its relations to the Bible words “sheol” and “hades.”[23] But Russell never answered White’s 18 questions, nor did he reply to any of the twelve passages discussing “gehenna.”

What was the lasting impact of the debate? The debate was important due to the fact that it was one of the first debates challenging the teachings of the Millennial Dawn Students and Charles Russell. This early debate helped many Bible students to see the unorthodox nature of Russell’s teachings, and his over-emphasis on rationalism. The book published by Fred Rowe went through several printings.

Perhaps the most important development of the debate was its contribution to the self-awareness of the churches of Christ as a distinct people, separate from the Christian churches in Cincinnati. As the 20th century unfolded, all of the congregations in the city had followed the “new order of things,” as John Rowe had called them.[24] Of those pleading for the “ancient order of things,” thee were only ten members meeting in a rented hall. It is clear that one of the intentions of those who had proposed the debate were to draw attention to the plea for New Testament Christianity and to re-invigorate the church in Cincinnati. At the beginning of his first speech on the last night of the debate, White called attention to the fact that several Christian Church preachers in the Cincinnati area had taken out ads in secular papers to publish their opposition to the debate. White said these men were operating out of fear that the organizers of the debate would gain a foothold in the city. White read the resolutions in which these preachers sought to distance themselves from any association with him.

We, the ministers of the Christian Churches of Cincinnati and vicinity, publicly state that we knew nothing of the proposed discussion until we read the announcement made through the secular papers. (White remarked that this was strange since a copy of the debate propositions and a personal letter had been sent to the Christian Standard, one of the largest circulating papers among the Christian Church). The Rev. L. S. White, is unknown to any of us, save one, either personally or by reputation. We are now informed that he belongs to a small ‘anti’-wing of the church and in no way represents the great brotherhood of which we are a part. The questions to be affirmed by Rev. White are not peculiar tenets of the Christian Church, and upon most of these questions, as in nearly every religious body, there is no unanimity of belief among the disciples.

Since so many vital problems press upon the attention of Christian people in the present, demanding solution; since so much practical Christian work calls with unprecedented necessity for laborers, and waits for willing hands, we deplore the proposed discussion of some of the questions named. We feel confident that the whole undertaking will prove barren of any permanent results which could be termed beneficial.[25]

White said that this was a “strange inconsistency,” because he and preachers like him, were still counted among Christian Church preachers and had their names included in their “year book,” yet he was being repudiated by them publicly when he came “to contend for the simple truth of the New Testament.” White went on to conclude:

I want it distinctly understood that, no difference who may be against us, we are here to contend for the truth, not simply as it may be opposed by Elder Russell, but against man’s teaching in any form which dares to go beyond the New Testament order of things.[26]

White always preferred to follow his debates with an evangelistic meeting. He remained in the city for five consecutive Sundays. Borrowing the Central Presbyterian Church building, White preached to crowds of 75 to 150 who came to hear him. The meeting resulted in 24 additions to the little band of brothers in Cincinnati.[27] Continued follow up to the work by other interested preachers brought new life to the work of the churches of Christ in Cincinnati.

The Wallace-Jones debate (Oral debate, August 1932). “The colorful Texas preacher J. D. Tant claimed that for very person who would to a protracted meeting, four would attend a religious debate. He also claimed that the number of converts from a debate was 500% higher than from any other means.”[28] The Wallace-Jones debate at Moundsville, West Virginia was a prime example of Tant’s claims.

The debate at Moundsville was the result of a challenge issued by Sam P. Jones, a Christian Church preacher visiting the area, proclaiming his “seven arguments in favor of the use of the instrument in worship to God.” Jones, a self-styled “walking Bible” held a series of meetings in the Upper Ohio Valley calling for member of the churches of Christ to “put up or shut up” regarding the question of instrumental music used in worship. The church of Christ meeting in Moundsville took Jones’ challenge and asked Foy E. Wallace, editor of the Gospel Advocate in Nashville to represent them.[29] Wallace accepted the challenge, denying biblical authorization for the instrument, while Jones affirmed it. The debate was held at the Camp Ground auditorium for five nights from August 16th through the 20th. Attendance for each night was estimated between 2500 and 3000.[30]

The debate received widespread coverage. Reports appeared in church papers like the Gospel Advocate and Christian Leader. It was also covered in secular newspapers such as the Moundsville Daily Echo and the Wheeling Intelligencer. More than 30 preachers from several states came to hear the debate.

The debate proved to have all the inflammatory elements that detractors of debating use against its propriety. Audience members expressed their emotions in several outbursts during the speeches. One night Wallace had to be escorted through an angry mob by West Virginia state troopers. On the last night of the meeting, the wife of Sam Jones shouted to Wallace that she could reply to his questions. Wallace replied by quoting the Apostle Paul, “Let your women keep silent in the churches . . . And if they will learn anything, let them ask their husbands at home. (1 Cor. 14:34-35).” Wallace then added in a jab directed against his opponent, “Perhaps Sister Jones knows her husband does not answer questions.”[31]

The significance of the debate is seen in the fact that the proposition discussed demonstrated that the question of instrumental music was far from a decided issue for many people in the area. There is a tendency among some today to think that U. S. Census office recognition of the division between churches of Christ and the Christian church in 1906 officially marked the separation between the two religious bodies. But the Moundsville debate showed that this recognition took a long time to be felt in many regions throughout the country.

The debate also signaled that there were individuals who were open to study on the issue of instrumental music, and its larger issue of the necessity for authority in all Christian proclamation and practice. The debate permitted this pursuit of truth and in the words of West Virginia preacher Ira Moore, some people for the first time were made aware of “the gravity of the sin of adding a human requirement to the Divine.”[32]

For those skeptical regarding the effectiveness of debating, it should be noted that several prominent members of the McMechen Christian Church, whose meeting with Jones had triggered the debate, renounced the use of the instrument, and identified themselves with the Moundsville church of Christ. Among them was a leading elder by the name of Siburt. His son, Charles Austin became a prominent preacher in Texas. Years later he wrote, “I was reared in the Christian Church. My family was led out of it through personal work of C. D. Plum and debate on Instrumental Music by Foy E. Wallace and Sam P. Jones in Moundsville, W. Va.”[33]

Conclusion

Debating has declined in practice and importance today. Different social conditions have contributed to this decline. Debating, both religious and political, was imminently more popular in the era before the advent of radio and television. Not only was it a discussion aimed at truth and understanding, it was also a form of entertainment which added variety to life’s routine.

Debates of previous generations have been judged to have yielded dubious results by some historians. Part of this doubt may arise from attitudes now held by the historians. The post modern attitude believes that truth is illusory and concludes that pursuit of truth is a chasing after the wind. There is also an attitude currently prevalent in which individuals decline to have their views critically examined and thus, they are unwilling to believe debating can do any good.

Debate, in and of itself, does not generate controversy or inject military imagery into religion. Religion, if it has any truth claim, will be controversial. And while it is needful and correct to speak of the relational aspect of Christianity, it also must be acknowledged that the soldierly dimension of Christianity is found in the pages of the New Testament. Every Christian needs to put on God’s armor and stand for truth (Eph. 6:10-18). All Christians must “fight the good fight of faith.” (1 Tim. 6;12; 2 Tim. 4:7). As Peter admonished, Christians must be able to give reasons for their hope with a gentle and humble spirit (1 Pet. 3:15). Not everyone will have the temperament or training for debating, but saints must not forget that they are also called to be soldiers.

The debates which were held in the Upper Ohio Valley in the early part of the 20th century grew out of a legacy tracing back to the days of Stone and Campbell. The individuals who followed in their footsteps clarified views on the issues debated and significantly contributed to the self-awareness and identity of churches of Christ in the region. However that identity and awareness might be judged today, the protagonists of the era, and their audiences, believed that the debates were worthwhile and contributed to the growth of churches of Christ in the century.

[1] Bill Humble, Campbell and Controversy, (Indianapolis: Faith and Facts Press, 1986 reprint of 1952 edition): 283.

[2] E. Brooks Holifield, “Debates, Debating,” in The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement, eds. Douglas A. Foster, Paul M. Blowers, Anthony L. Dunnavant, D. Newell Williams, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004): 262.

[3] James P. Swinney, “A Survey of Religious Debate Practices Among Ministers of the Churches of Christ – part Two,” Restoration Quarterly vol. 9 no. 2 (1966): 91.

[4] Earl West, The Search for the Ancient Order, vol. IV, (Germantown, TN: Religious Book Service, 1987): 222.

[5] Swinney, 94.

[6] Don Haymes, “Debates, Interdenominational,”in Encyclopedia of Religion in the South, ed. Samuel S. Hill (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1997): 196.

[7] Michael W. Casey, Saddlebags, City Streets, & Cyberspace, (Abilene: ACU Press, 1995): 48.

[8] Alan Highers, “Set for the Defense of the Gospel,” The Spiritual Sword vol. 36 no. 1 (October 2004): 7.

[9] Barton W. Stone, “A Letter to the Church of Christ Scattered Abroad Throughout the United States of America,” Christian Messenger vol. 14 no. 4 (August 1844): 117.

[10] Alexander Campbell, The Christian System, (Nashville: Gospel Advocate, 1964 reprint of 1835 edition): xii.

[11] Alexander Campbell, “Notification,” Christian Baptist vol. III (August 1, 1825): 177.

[12] Alexander Campbell, “Prefatory Remarks,” The Millennial Harbinger vol. 1 no. 1 (January 4, 1830): 8.

[13] I. B. Bradley, “J. W. Shepherd Leaves the South,” Christian Leader April 13, 1915: 9.

[14] J. W. Shepherd, “A Trip South,” Christian Leader August 17, 1915: 9.

[15] A. A. Bunner and Ben E. Rich. The Bunner-Rich Debate, (Chicago: Henry C. Etten & Co., 1912): 5-6.

[16] Thad Hutson, “Considerations,” Christian Leader May 12, 1925: 6.

[17] Mrs. U. G. Wilkinson, “Why We Believe in Debates,” Christian Leader May 10, 1932: 16.

[18] Rowe had merged his paper The Christian Leader with James A. Harding’s The Way in 1904 with Harding as co-editor with James S. Bell. For the next 9 years the paper was known as The Christian Leader and the Way.

[19] Fred Rowe, “Publisher’s Announcement,” in Moore-Noble Discussion, (Cincinnati: F. L. Rowe publisher, 1910): 2.

[20] Russell-White Debate, (Cincinnati: F. L. Rowe, Publisher, 1912 reprint of 1908 edition): 64-68.

[21] Ibid, 73.

[22] Ibid, 75.

[23] Ibid, 79.

[24] Earl West, The Search for the Ancient Order, vol. II, (Indianapolis: Religious Book Service, 1950): 224-25.

[25] Ibid, 178-79.

[26] Ibid, 179.

[27] F. L. Rowe, “The Meeting in Cincinnati,” Christian Leader and the Way, (March 31, 1908): 5.

[28] Michael Casey, op cit, 47.

[29] F. B. Syrgley, “The Moundsville Debate,” Gospel Advocate September 8, 1932: 988, 1000.

[30] C. D. Plum, “Report on the Moundsville, W. Va. Debate,” Gospel Advocate September 8, 1932: 1004.

[31] Syrgley, op cit, 988.

[32] Ira C. Moore, “The Jones-Wallace Debate,” Christian Leader September 6, 1932:4-5.

[33] “Charles Austin Siburt,” in Preachers of Today, vol. I. Batsell B. Baxter and M. Norvel Young, eds. (Nashville: The Christian Press, 1952): 311.