SINGING IN THE RESTORATION MOVEMENT

By Bruce Daugherty

(originally presented at Cold Harbor, Va lectures 2008)

Recent reports of congregations adopting the use of instrumental music in their worship demonstrate the need for the studies in this lectureship. When one investigates the rationale offered for the departure from convictions and practices long cherished, it becomes apparent that many Christians today are unaware of the history of the issue within the Restoration Movement. It is hoped that this study will help the reader to gain an appreciation for the importance of singing as it has been practiced in the Restoration movement. Awareness of the value of this heritage may help those who are tempted to trade away things eternal for the temporary. “Lest there be any fornicator or profane person like Esau, who for one morsel of food sold his birthright. For you know that afterward, when he wanted to inherit the blessing, he was rejected, for he found no place for repentance, though he sought it diligently with tears.” (Hebrews 12:16-17, NKJV).

Before studying the doctrinal and practical insights of the pioneers regarding singing, it is helpful to re-examine what is meant by the Restoration principle. The principle is essentially the seed principle. In the physical world, God made seed that produces after its kind (Gen. 1:11-12). This power within seeds has been demonstrated repeatedly, even after centuries of dormancy. In the parable of the soils, Jesus said, “The seed was the word of God” (Luke 8:11). Thus, the spiritual reproductive power of Christianity is found in the Word of God. The plea to restore New Testament Christianity is a commitment to follow the scriptural patterns and divinely approved examples of the Apostles and first Christians. It is the spirit of Paul’s plea: “Imitate me, just as I also imitate Christ.” (1 Cor. 11:1).

The Restoration Principle Applied to Music in Worship

Looking to the Scriptures, the Restorers followed Paul in his example of singing in worship. “I will sing with the spirit, and I will also sing with the understanding” (1 Cor. 14:15). Two important items were elicited from this statement by the Restorers. First, they were conscious of following Paul, not David. “Christians should follow Paul, who sang, and not David, who played . . .” (Tomson, 145). Their appeal was to the New Testament, not the Old for their practices.

J.W. McGarvey said,

How, then, are we to decide whether a certain element in Jewish worship, or in the worship of heaven, is acceptable in the Christian church? Undoubtedly we are to decide it by the teaching of the New Testament, which is the only rule of practice for Christians. Whatever is authorized by this teaching is right, and whatever it condemns is wrong in us, whether it belongs to the service of the Jews or the service of angels. (McGarvey, Millennial Harbinger, 1864:511-12).

Second, the positive action to sing was exclusive. To sing was authorized by the passage. To play was unauthorized. “Paul says, ‘I will sing,’ but he does not say: I will play upon an organ, harp, or other instrument.” (Tomson, 145). To affirm that the use of instrumental music is optional because the passage did not contain an explicit condemnation of the instrument, carried “unwelcome consequences” to the mind of McGarvey.

Shall we thence argue that, in the silence of the New Testament, these facts should be taken as an indication of the divine will, and, like the Catholics, shall we burn incense in our public worship? Shall we, for the same reason, keep lamps or candles burning in our churches, and array our preachers in gorgeous robes? For all these the argument is valid, if it is valid for instrumental music. If, therefore, we adopt the latter, we dare not pronounce any man or church unscriptural in this practice that adopts the other three. (McGarvey, Millennial Harbinger:512).

To sing with understanding was to know what was to be sung: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs (Eph. 5:19; Col. 3:16). Tillit Teddlie gave this word of instruction regarding the selection of songs to be sung.

Song leaders should be very discriminating, very careful, in selecting songs for the divine service. They should never select a song for the rhythm, or harmony, but solely on the merits of meeting the New Testament requirement, namely, that it will teach and admonish the body of Christ. (Is Any Cheerful?)

To sing is necessary in order to teach and admonish one another in psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs (Eph. 5:19; Col. 3:16). Mutual teaching and admonishment is accomplished by singing. This was something that the instrument could not do. “Singing informs the understanding and excites our emotions also; but instrumental music will not do the former, even if we admit it will do the latter” (Tomson, 146). The inarticulate sounds of instruments cannot accomplish the teaching purpose and aspect of singing.

Since we are commanded to teach and admonish one another in psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs, every song which we sing should have an admonition, an appeal to the heart and conscience for greater consecration and devotion to God. . . . Thus by speaking in songs we may teach and admonish one another, by bringing the thoughts and feelings of the heart into harmony with the sentiment of the songs. (Teddlie, Come Before His Presence).

Testimony of the Early Days

“In earlier years of the present Reformation there was entire unanimity in the rejection of instrumental music from our public worship. It was declared unscriptural, inharmonious with the Christian institution, and a source of corruption.” (McGarvey, Millennial Harbinger: 510). This unanimity regarding singing in worship had a sociological factor. The use of instrumental music in worship was rarely discussed by the first generation leaders in the movement. “For the pioneer generation this was not an issue, as most early nineteenth-century American churches sang unaccompanied.” (Thomas, 410). Later, when the frontier faded and social conditions changed then the issue became problematic.

But the practice of singing in worship was also a result of doctrinal convictions. Study in the word of God and a determination to submit to it motivated the early leaders. Alexander Campbell expressed his view of singing and the power of the hymnal in an editorial in his paper:

We are divinely commanded to teach and admonish one another in psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs –to sing with grateful hearts, thus making melody in the ears of the Lord of host. The subject matter of the Christian psalter, psalm, or hymn, is therefore of the first importance; as, next to the Bible, no book in the world has such influence on the heart. (Millennial Harbinger 1842:229-31).

Later Campbell would respond to a question about instrumental music in the worship services. Campbell said that only Christians who had lost their spiritual sensitivity would need the aid of instruments to stir their carnal hearts. To spiritually minded Christians, however, “such aid would be as a cowbell in a concert.” (Millennial Harbinger 1851:582).

Barton W. Stone also had opportunity to comment on the importance of the song service.

There is no part of divine worship more abused than singing. Every sect has a hymn book shaped and adapted to its peculiar systems of opinions, and these opinions are as variant as their names. Can this babel of confusion be acceptable to God? Can he be pleased with such worship? (Stone, CM:253).

Stone was commenting on the confusion of sectarian doctrines taught in hymn books. The way to avoid this confusion would be to have hymnals with texts conforming to the word of God. Stone gave several examples of error taught in song and then concluded his article stating, “These remarks are made to elicit investigation on these subjects—and if possible, to lead the religious to reformation from all errors in doctrine and practice.” (Stone, 255).

Since Campbell and Stone realized the teaching aspect of the song service was so important, both men produced hymnals whose songs would have texts in accord with their understanding of Scripture. Eventually their hymnals would be combined in an edition titled, Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs, Original and Selected – Compiled by A. Campbell, W. Scott, B. W. Stone, and J. T. Johnson – Bethany, Va. 1834. (McCann,29). Despite some initial friction in collaboration, the songbook enjoyed a long life of service among congregations begun by the impetus of the Restoration movement. (Thomas, 409).

Pictures of Singing in the Assemblies

The literature of the Restoration movement gives glimpses of the place of singing in worship assemblies. Moses Lard described for his readers “his church,”

In their order of worship several things strike me as noteworthy. In their singing, which I pronounce excellent, I discover they prefer the older type of tunes. “Old Hundred,” for instance, seems a favorite with them, and in almost all their Lord’s day meetings I notice they sing “Safely through another week.” They seem, too, to be much attached to that fine old piece, “O, though Fount of every blessing.” In all this I must confess, I think their taste excellent. Those grand old airs are the very melody of the soul, and those matchless hymns the very utterance of the pious heart. They all sing sitting. (Lard, 148-40).

The singing of the period was also described in a biography of Ben Franklin:

It can be remembered by many living men that in the earlier days of the Reformation the songs sung were very few in number, while the number of tunes employed was still less. In the enthusiasm of the days when nearly all meetings were revivals, the high flow of spirits led everybody to sing. Hymn-books were almost unknown in many places. The leader and one or two others sometimes had books, but the masses of the members had memorized the few hymns which were used and sang without books. (Franklin and Headington, 114).

In addition to memorization, the practice of “lining” the text of the hymns was common. “In the early days of the restoration movement there were few hymns and little training in sacred music. Consequently, the preachers would often “line out” the hymns from the pulpit. This meant singing a line of music to which the audience would respond.” (West, Trials, 240). Alanson Wilcox recalled a humorous example of “lining” a hymn. The song being lined began, “I love to steal away awhile.” The leader began by reading the line, “I love to steal . . .” The members remained quiet. The leader repeated his opening line several times but without the congregation joining in. Finally the preacher stood up and said, “Considering the propensities of our brother, let us pray.” (Wilcox, 149).

Gospel preacher J. P. Kimbrell shared his memories of singing in worship:

The finest and most spiritual congregational singing I have ever heard was during my school days in Lawrenceburg, Tenn. It seemed that the spirit of worship was in the air when that congregation began to sing. They sang the old hymns that feed the soul, and those were the good old days when we sang with the spirit and the understanding. (Christian Leader, 8-9-1921:1).

To remedy shortcomings in the song service, singing schools were a popular practice. F. D. Syrgley recalled his summer time experiences in the South:

We had no Sunday schools, but singing schools flourished in every neighborhood. Ten days was the usual length of such schools, . . . We met at eight o’clock in the morning, brought our dinner with us, and sang till five o’clock in the evening—nine hours a day, hard singing, every day in the week for five weeks on a stretch right through the hottest part of the summer! That’s the way I learned to sing! (Syrgley, 213-14).

Ben Franklin’s early paper The Proclamation and Reformer carried a musical department headed by A. D. Fillmore for the purpose of improving congregational singing. (Franklin and Headington, 197). Franklin was able to see the need for training in singing. “It is lamentable to see the negligence of the brethren in cultivating their talent for singing. It might truly be said, that, of all the delinquencies which have obtained amongst religious people, this one is transcendent.” (Franklin and Headington, 89). After giving a lengthy example of incompetency in song leading, Franklin made his appeal for training in song:

It is just because no effort is made to learn to sing; for there are some that could learn in every congregation. Let them practice at home, and assemble for an hour before meeting time and practice, and so develop a love for singing, and they will soon be able to sing a great variety of our excellent songs and hymns. When you go up to the house of God, go with the intention of mingling your voice in the praises, and sing with the spirit and with the understanding. (Franklin and Headington, 89-90).

Franklin’s choice of A. D. Fillmore to head the music department in his paper was fortunate. Fillmore had been a music teacher before his conversion. He was blessed with musical skill and ability that was enhanced by an adequate education. Fillmore’s life was brief but he wielded a great influence through his instruction in song and the publication of several hymnbooks. High praise was given to Fillmore’s hymnbooks:

The “Christian Psalmist,” published by Leonard and Fillmore, appeared when the latter was only twenty-four years of age. It was greatly revised and improved in subsequent editions, and probably had a more general circulation than any other of his publications, although its merits were certainly inferior to the “Harp of Zion,” and the “Christian Psaltery.” The “Psalmist,” however, met a great want, and appeared without a rival. (Franklin and Headington, 199).

The work of Fillmore had a lasting influence. “Fillmore published many rudiment books, Sunday school hymnals, and other song books. By the age of 30 he had established a permanent reputation.” (McCann, 33). Fillmore’s sons continued their father’s work as they established Fillmore Brothers Music Co. in Cincinnati and published hymnbooks and musical instruction books into the early 20th century. (Wilcox, 152-53).

Insight into the Instrumental controversy

Sociological conformity was a factor with the introduction of instrumental music into the worship assemblies. “With growing prosperity, improved schooling, and increasing cultural sophistication came the idea of introducing instrumentation.”(Thomas, 410). In the words of J. S. Lamar, use of the instrument was “an inevitable consequence of growth and culture.”(Ferguson, 414). To progress with the spirit of the age was to adopt the use of instruments in worship. But there was more to the controversy than just joining the trends of the times.

Whatever part economic and cultural factors played in the controversy over the presence of instruments in worship, many participants soon observed that an important factor producing division was different approaches to scripture authority and interpretation. Opponents saw the silence of Scripture as prohibitive, whereas supporters saw it as allowing liberty. (Ferguson, 415).

When the controversy occurred over the introduction of instrumental music into the worship assembly Ben Franklin was “the eye” around which the storm swirled. (West, Eye, iv). The writings of the preacher from Indiana give insight into the controversy of the period. Shortcomings in the song service were used as a reason for bringing in the instrument. Joseph Franklin shared his father’s confidences. “In the last years of his life, after instrumental music had been appealed to as a remedy for the deficiency of the churches in singing, he frequently expressed . . . his profound regret that more attention had not been given to the importance of singing as part of the worship of God” (Franklin and Headington, 90). Franklin’s first article on the subject echoed Campbell’s early view, that the use of the instrument might be advantageous “where the church never had, or have lost the spirit of Christ,” or, “if the church only intends to be a fashionable society, a mere place of amusement.” (Franklin and Headington, 409).

Franklin tried to get his brethren to see what was really important in the song service.

We ought not to enter into it with the heart set on music, either instrumental or any other sort, but on God and gracious and merciful Lord Jesus the Christ. The words ought to be read frequently and a few words of comment on them, calling attention to the sense, the praises, thanksgiving and supplication. . . . The theme of the song is the great matter. To sing with the spirit and the understanding is commanded, and to teach and admonish in singing is also commanded. The main body of the singing now done is not with the spirit or the understanding, nor is anything taught or any one admonished. This is no worship. Singing merely to make music is no more worship than performing on a piano or violin. (Franklin, Gems, 232-33, emphasis in original).

To those who claimed that the use of the instrument was part of progression, Franklin saw it as a move backward. This was to lose sight of the Restoration plea, and lose all that had been gained in striving for New Testament Christianity.

What a farce for men to be talking of progress, going on to perfection, keeping up with the age, etc., etc., when they are giving up and retrograding from the grandest progress possible to men-the progress up to the ground consecrated by the feet of the apostles and first Christians. Talk of progress when going back to the feeble and exploded schemes of sectarians and patronizing their shallow devices! Progress, indeed, to turn away from the holy gospel, the power of God to salvation, and scheme to catch people and draw them in by the blandishments of fine houses, theatrical, musical shows and clerical pretentions! (Franklin, Gems, 46-47, emphasis in original).

Despite strong and persistent editorials, Franklin found it hard to stem the tide pressing for inclusion of the instrument. Rather than seeing what was gained, Franklin spoke of what was being lost in the introducing of the “new element” in worship.

When it comes to the point that their feelings are disregarded, all their entreaties and expostulations being set aside and a new element in the worship, not named by their gracious Lord nor His apostles, is forced into the worship on the Lord’s Day and imposed on them by a majority, their peace and happiness will be ruined. (West, Eye, 240).

In addition to this disregard for the instructions of the Lord and His apostles, and the feelings of their brethren, Franklin charged that this majority in favor of the instrument left the impression that they loved the instrument more than their brethren. “When it comes to this, love, Christian affection and attachment have pretty much disappeared. The tie that bonds their hearts in Christian love and affection is broken.” (West, Eye, 241).

When the majority in the church at Charleston, Illinois introduced an organ, its opponents wrote to Franklin, desiring to know what action to take. Franklin laid out his formula:

- Be guarded in language . . . Be careful, then and not say anything to wound the feelings of any, or you may find it in the way when the organ trouble may be removed.

- Do not denounce anybody, nor pronounce anything severe on any one.

- Be firm and decided in reference to the one thing—the requirement to submit to the use of the organ in worship. Tell all that you cannot submit to it. (emphasis in original).

- Do not decide to stay at home, and wait for something to turn up, nor make it an excuse for going out of the church.

- Declare non-fellowship with no one; say nothing about refusing fellowship, or leaving the church, or withdrawing from it. But deliberately and quietly meet in another place, and worship regularly according to the Scriptures. Attend to the breaking of the loaf, the apostle’s teaching, prayers, praise, and contribution. Worship in spirit and in truth. Talk of no new church, “second church,” nor anything of the kind. . . . If the evil shall at any time be removed, there will then be nothing in the way of all meeting and worshiping together. If the evil shall never be removed, your way will be clear to go on and build up the kingdom of God in the community, set the congregation in order according to Scripture. (Franklin and Headington, 412-14).

Toward the end of his life, Franklin put together a sermon in which he summarized much of what he had been saying for forty years regarding the Biblical authorization for singing in worship and why he believed it to exclude the instrument. Franklin made it clear that the point to consider was not music or singing in and of itself, but “singing in obedience to the command of God.” (Franklin, Gospel Preacher, 415 – emphasis in original ). For Franklin the question was of worship according to divine authority.

They do not sing because they love to sing, or because they love music, but because they love God and delight to do those things that are pleasing in his sight; to obey his command; to sing, making melody in their hearts to the Lord. In obeying this command their minds are not taken up with a bundle of note books, tune forks, or with music at all; but with praising God, thanksgiving, exhortation, admonition, and teaching. (Gospel Preacher, 415 – emphasis in original).

After citing Colossians 3:15-17 and Ephesians 5:18-20 as the explicit authority for singing, Franklin pointed out the truths contained in these passages. First he noted that singing was the action commanded, or “the precise thing to be done.” Second, he said that “we are to teach one another in singing.” Third, there was the purpose of mutual admonition. Franklin denied that the instrument could fulfill the purposes of teach and admonish.

In his sermon Franklin also replied to those who asked for Scripture in the condemnation of the instrument. Franklin replied, “It is not forbidden. Neither is infant church-membership forbidden; but the Pedobaptists have no Scripture for infant membership!” For Franklin, the exclusion was found in the fact that there was no example of the Lord, His apostles, and their followers using instruments.

But did our Lord utilize it (the instrument)? No; he established his religion in a country where all worshipers, of all kinds, used instruments in worship, but left the instruments all out! He did not leave them out because there were not plenty of them, nor because he could not get them, nor because they were not popular; but because he did not want them. This is a divine prohibition. (Gospel Preacher, 419 - emphasis in original).

Franklin went on to say that instruments were brought into Christian worship only after the great apostasy. The fact that instrumental music was introduced many centuries after Christ and the apostles ought to have been reason enough for excluding the practice if one was really concerned with “primitive Christianity” and the “ancient order” according to Franklin.

In the next part of his sermon, Franklin examined some of the arguments offered in defense of the instrument. He admitted his position was unpopular and went against the tide of current society. But he believed he was on the safe ground.

For those who appealed to the words of the psalms, “Praise God on the harp,” Franklin responded that their appeal needed to include trumpet, psaltery, timbrel, stringed instruments, cymbals, and dance as well as the organ. If one were going to appeal to the psalms for authorization then one had to acknowledge that all of the instruments plus dance were commanded and not left to the realm of opinion or expediency. To select only one or some of the items commanded was not obeying Scripture. But if dance and several instruments were excluded on the grounds that they were part of the Old Dispensation then Franklin replied, “Then away with these instruments, and the dance, too, in worship; not some of them but all of them, as things not belonging to the New Dispensation at all.” (Gospel Preacher, 425- emphasis in original).

Others looked at the instrument as an expedient, or a thing of indifference whose use was optional. Franklin then asked, “Why, then, press a thing indifferent into the church, against the will of good members, and create contention and strife? Why be so persistent in this, as to push it in and split the church in two?” But for Franklin, the instrument was not a matter of indifference.

We have considered it for many years, and looked at it from every possible angle, and tried it in every possible way, and our judgment, our deepest and most settled convictions are against it, as an innovation, a corruption of the worship, subversive of the divine purpose in worship—to teach and admonish in song; carnalizing the worship, by turning it into an entertainment, a mere musical attraction, an amusement. (Gospel Preacher, 426 - emphasis in original).

Franklin then observed that those who asked to be given freedom to use the instrument in public worship compelled all worshipers to submit to its use, or not worship at all. Far from being an expedient, it became a matter of compulsion. But there was a consequence to this expedient.

In doing this, in the place of making the use of the organ a matter of indifference, you make it a matter of indifference whether we shall adhere strictly to the law of God in worship, do the things commanded, add nothing, or take nothing away from what is clearly prescribed in the law of God. (Gospel Preacher, 429 - emphasis in original).

Franklin said what this demonstrated was indifference to the law of God! He went on to say that the indifference argument was made so that opponents would submit meekly to the practice. In Franklin’s experience this matter of indifference never led the proponents to not introduce the instrument for the sake of peace.

As Franklin drew his sermon to a close, he pointed out that the admission of the instrument on the principle “not forbidden in Scripture,” opened a flood gate for all innovations. Acting in accord with this principle would “surrender every principle we hold, and leaves us without a reason for our existence as a religious body.” (Gospel Preacher, 431).

Practical Measures to Preserve Singing in Worship

Despite the efforts of Franklin, Moses Lard, J.W. McGarvey, David Lipscomb and many others of their generation, the Restoration movement divided between those who accepted the use of instrumental music and the missionary society and those who did not. Many third generation Restoration leaders who experienced the bitterness of the division took practical measures to avoid a repetition of those days. Deeds to church buildings appeared with “instrument” and “society” clauses to prevent the loss of property. Debates, once limited to those of denominational backgrounds, now were also conducted with “erring brethren.” Numerous articles were written to instruct on the importance of the issues and being able to answer the arguments of instrumentalists.

Fred Rowe, owner of the Christian Leader, did not put much stock in efforts to reunite with what he called “society brethren.” When the North American Christian Convention was proposed for Indianapolis in October 1927, overtures were made to various representatives in churches of Christ to attend. Rowe shared his feelings:

A few of our honest but misinformed brethren have been made to think that these society brethren would consider giving up their practice of innovations, particularly the use of the organ, in order that we “might be one.” I ventured the statement that when these people know this crowd as well as I believe I do, that they will discover that it is a waste of time and effort to expect anything from them. They are absolutely “wedded to their idols,” and the only union that will ever be accomplished is a union based on their own platform. (Rowe, 8).

Rowe knew of that which he spoke. He had worshiped five years with instrumental congregations in Cincinnati before making the painful decision to part fellowship. Rowe noted that the “society people” never accepted any responsibility for the division which they characterized as being over “non-essentials.”

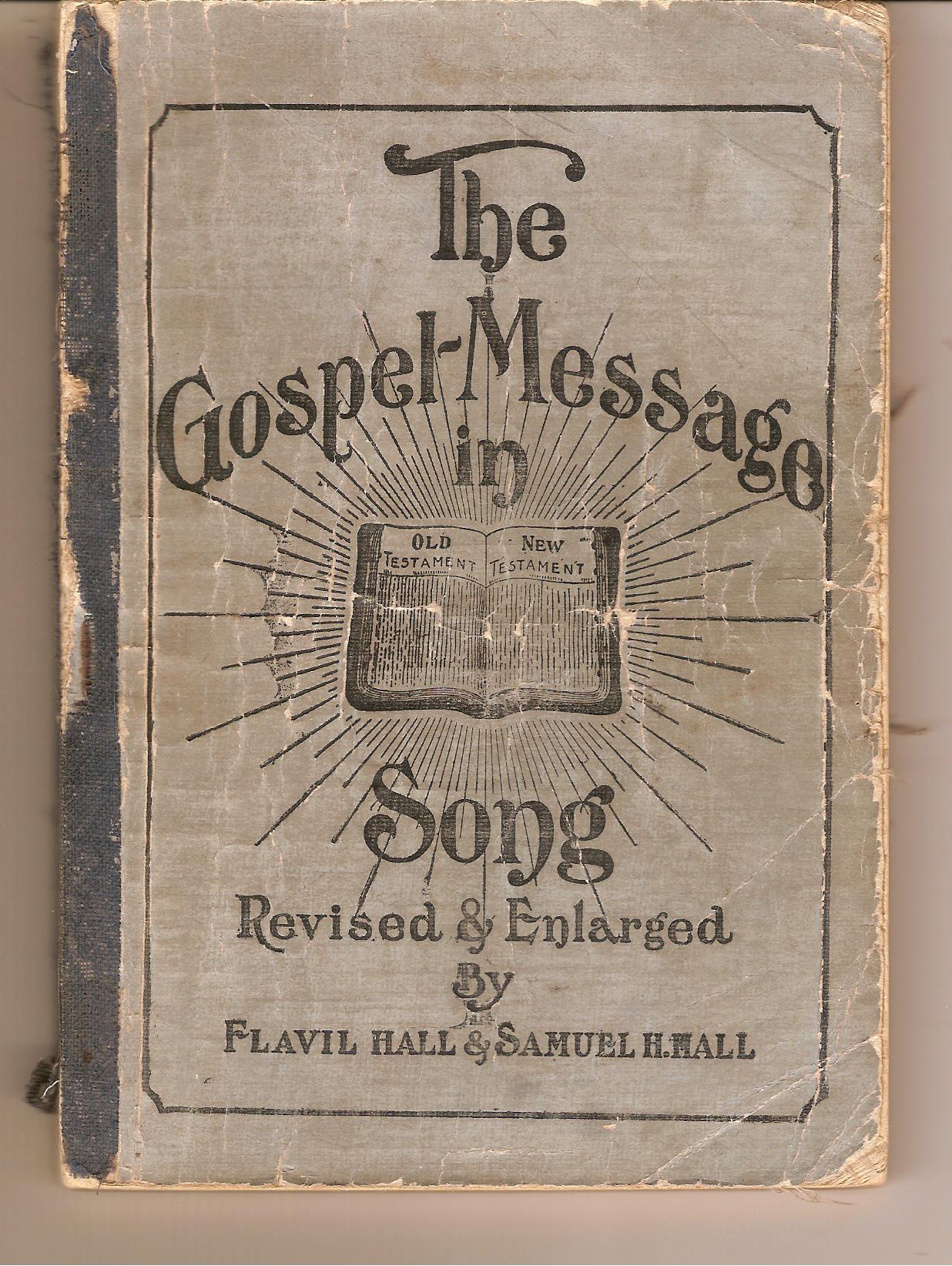

Evangelist Flavil Hall of Georgia, a capable preacher and hymn writer frequently addressed singing in his columns in the Christian Leader. Hall wrote, “Faithful disciples should be able to meet the arguments of the members of the apostate Christian Church in justification of instruments of music in the worship and of the humanly organized societies.” (Hall, July 20, 1915: 10). But Hall’s best contribution to the preservation of singing in worship was through his collaboration with fellow evangelist S. H. Hall in the production of a hymnal.

Prior to 1908, Flavil Hall had authored many hymns, but none had ever been included in a hymnbook by his brethren. At the invitation of a fellow preacher in Georgia, Flavil Hall came to Rockmart, Georgia to assist in a gospel meeting. S. H. Hall had been invited to hold the meeting at the invitation H. M. McCrae. McCrae was the only member of the congregation who believed that singing was authorized by the New Testament and that the instrument was unauthorized. Because the congregation knew that McCrae had invited Hall to hold the meeting, most of the congregation was against the meeting. In order to overcome the prejudice against them and to change the thinking of the members, the Halls let it be known that their purpose in meeting at Rockmart was to compile a songbook. S.H. Hall wrote of the experience: “So I wrote him and asked that he collect some three or four hundred songs with the idea of expressing in song the full gospel of Christ; and then come to Atlanta and we would compile a book to use in our work.” (S.H. Hall, 79, emphasis in original). Hall elaborated on the impact of the songbook on the Rockmart congregation.

There can be no doubt that Flavil and I being there for the purpose of finishing the compilation of our first song book had much to do with our success. For it diverted the minds of the people, to a degree, from a revival to the idea of getting out a book which taught the gospel in song as fully as we teach it in sermon. Comments were made on some of the songs, and naturally the idea got into the minds of the people that we must be as careful about the wording of the songs, being as sound as our sermons are supposed to be. (S. H. Hall, 81, emphasis in original).

Flavil Hall offered his view of what the collaboration in song accomplished:

S. H. Hall encouraged me, helped me and lifted me in my efforts to use my talents in the ‘song world,’ when nobody else in the ranks of the disciples seemed willing to do it. Publishers I talked with thought nobody but a sectarian could be the musical editor of a song book for them. S. H. Hall said, “Go ahead and get the material ready and I will help you.” This he did, and when F. L. Rowe’s attention was called to our efforts and he saw the manuscript, we had another helper. For all this my gratitude shall not die. ‘The Gospel Message in Song’ was the first song book, with notes, that was ever edited by only the faithful disciples of Christ. The truth in its fullness has been sung as never before, and no other book has ever been more liked in words or music where the people have become really acquainted with it, and our books are following it. ‘Redemption’s Way in Song,’ and ‘Jesus in Song,’ are growing equally popular among good singers and lovers of the truth. (F.H. Hall, Christian Leader, August 31, 1915, 10).

Over the next 22 years, Flavil Hall would compile eight songbooks as well as his own Rudiment book for singing instruction. Wherever he would hold meetings he would always conduct a singing school. He believed that if congregations were going to avoid the innovation of the instrument being added to worship it would come through their training and involvement in learning to sing. Years later, S. H. Hall would write about his co-laborer: “I loved him and will ever remember the good he did in helping me to get song’s place in the heart of the members in Atlanta in early days of our work.” (S. H. Hall, 82).

Conclusion

To study singing in the Restoration movement is to gain an appreciation for a heritage that has sought to return to the New Testament for faith and practice. This heritage has garnered valuable insight into the place of singing in worship. Several lessons are offered from the insights examined in this study.

First, the Restorers viewed worship as regulated by the New Testament. Divine authority as expressed in the pages of the New Testament is the basis for worship. This “safe ground” of the teaching and examples of Jesus and His apostles viewed singing as authorized by Christ and instrumental music as unauthorized.

Second, the Restorers viewed worship as an activity of the mind and the heart. To “sing with the understanding;” “to teach and admonish in psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs” is to understand that the text is paramount in the songs. Musical consideration, whether vocal or instrumental, was secondary to the text. Mere musical exercise, vocal or instrumental, that did not engage the heart and mind, was not considered to be true worship.

Third, the Restorers viewed worship as being spiritual in nature. While the senses and emotions could be aroused by instrumental music, it was viewed as belonging to the fleshly dimension of man. For the Restorers, instrumental music was incapable of satisfying the spiritual dimension and requirement for acceptable worship.

Fourth, the power to conform to social and cultural pressure has always been strong in the Restoration movement. But Restorers were determined to follow the New Testament as they understood it, in spite of the pressure to go with the tide of the times. Enduring the ridicule and scorn of their contemporaries, they refused to return to the practices they had left behind in denominations.

Fifth, the Restorers believed that having a good hymnal and efforts to improve congregational singing were important deterrents to the introduction of the instrument in worship. Song services led by trained, effective men with song texts that lift hearts to the throne of God will build the spirit of worship in a local congregation.

But the lessons gained by the Restorers are of no benefit to those who are unwilling to listen to them. The self-imposed deafness of those under the tyranny of the contemporary robs one of the counsel and wisdom of the past. May God give each one of us a willingness to listen to their voices so that they may help us to resist the temptation to trade the eternal for the contemporary.

“Behold, a church of Christ so filled with the spirit and love of Christ that its songs become an uplifting to God, a sacrifice of praise to God continually, that is, the fruit of the lips which make confession to his name!” (Teddlie, Come Before His Presence).

References

Campbell, Alexander. “Christian Psalmody-No.1,” Millennial Harbinger 6, ns., 6, no. 5 (May 1842):229-31.

___________, “Instrumental Music,” Millennial Harbinger vol. 1, 4th s., no. 10 (October 1851):581-82.

Ferguson, Everett. “Instrumental Music,” Stone-Campbell Movement Encyclopedia, eds. Douglas A. Foster, Paul M. Blowers, Anthony L. Dunnavant, and D. Newell Williams (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 2004): 414-17.

Franklin, Ben, “Instrumental Music,” in The Gospel Preacher, vol. 2 (Delight, AR: Gospel Light Publishing Co, reprint of 1879 ed.): 411-432.

__________, A Book of Gems, J. A. Headington and Joseph Franklin, eds. (Nashville: Gospel Advocate, 1960 reprint of 1879 ed.).

Franklin, Joseph & J. A. Headington, Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (Rosemead, CA: Old Paths Book Club, 1956 reprint of 1879 ed.).

Hall, Flavil. “Field Notes and Helpful Thoughts” Christian Leader (July 20, 1915): 10.

__________, “Field Notes and Helpful Thoughts” Christian Leader (August 31, 1915): 10.

Hall, S. H. Sixty Years in the Pulpit (Rosemead, CA: Old Paths Book Club, 1955).

Kimbrell, J. P., “Church Music,” Christian Leader (August 9, 1921):1.

Lard, Moses E. “My Church,” Lard’s Quarterly vol. 1 (December 1863): 141-154.

McCann, Forrest. “Hymnals of the Restoration Movement,” Restoration Quarterly vol. 19, no. 2 (1976): 23-38.

McGarvey, J. W. “Instrumental Music in Churches,” Millennial Harbinger vol. 7 5th s. no. 11 (November 1864): 510-514.

Rowe, F. L., “Wedded to Their Idols,” Christian Leader (August 16, 1927):8.

Stone, Barton, “Singing,” Christian Messenger (August 1832): 253-55.

Syrgley, F. D. Seventy Years in Dixie, (Nashville: Gospel Advocate, 1954 reprint of 1891 ed.).

Teddlie, Tillit S. “Come Before His Presence With Singing,” Gospel Broadcast vol. 2 no. 1 (January 1, 1942): 7.

_________, “Is Any Cheerful? Let Him Sing Praise,” Gospel Broadcast vol. 2 no. 2 (January 8, 1942): 14.

Thomas, Theodore N. “Hymnody,” Stone-Campbell Movement Encyclopedia, eds. Douglas A. Foster, Paul M. Blowers, Anthony L. Dunnavant, and D. Newell Williams (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 2004: 409-11.

Tomson, J. H. D. “How to Sing,” in Gospel in Chart and Sermon, ed. J. J. Limerick, (Cincinnati: J. F. Rowe Publisher, 1897): 145-46.

West, Earl I. Ben Franklin: Eye of the Storm, (Germantown, TN: Religious Book Service, 1984).

_________, Trials of the Ancient Order, (Germantown, TN: Religious Book Service, 1993).

Wilcox, Alanson, A History of the Disciples of Christ in Ohio, (Cincinnati: Standard Publishing, 1918).