TWO EXTREMES

by Bruce Daugherty

(originally presented at Cold Harbor, VA lectures Nov. 2010).

Balance is an important word when considering an individual or a society. To be “unbalanced” is to be mentally unstable or deranged. One factor as to why individuals may lose their balance is by going to extremes. The ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle, taught his students in ethics to search for the “golden mean;” that is, the balance between the extremes of excess and deficiency (Wedin, 44).

Balance is also important in the life of the servant of God. Long ago, Joshua was told, “Only be strong and very courageous, that you may observe to do according to all the law which Moses My servant commanded you; do not turn from it to the right hand or to the left, that you may prosper wherever you go.” (Josh. 1:7, NKJV). Jesus had difficulties with extremists of his day, as the Pharisees and the Saducees both sought to attack Him (Matt. 22:23-40). The Pharisees represented an extreme that bound the oral tradition to the Torah, while the Saducees were another extreme that “loosed” the law by only observing the books of Moses. The Apostle Paul spoke of the testimony of his people, that they had a “zeal for God, but not according to knowledge.” (Rom. 10:1-2). Zeal is needed in the life of the Christian, but it must be a zeal tempered and guided by knowledge.

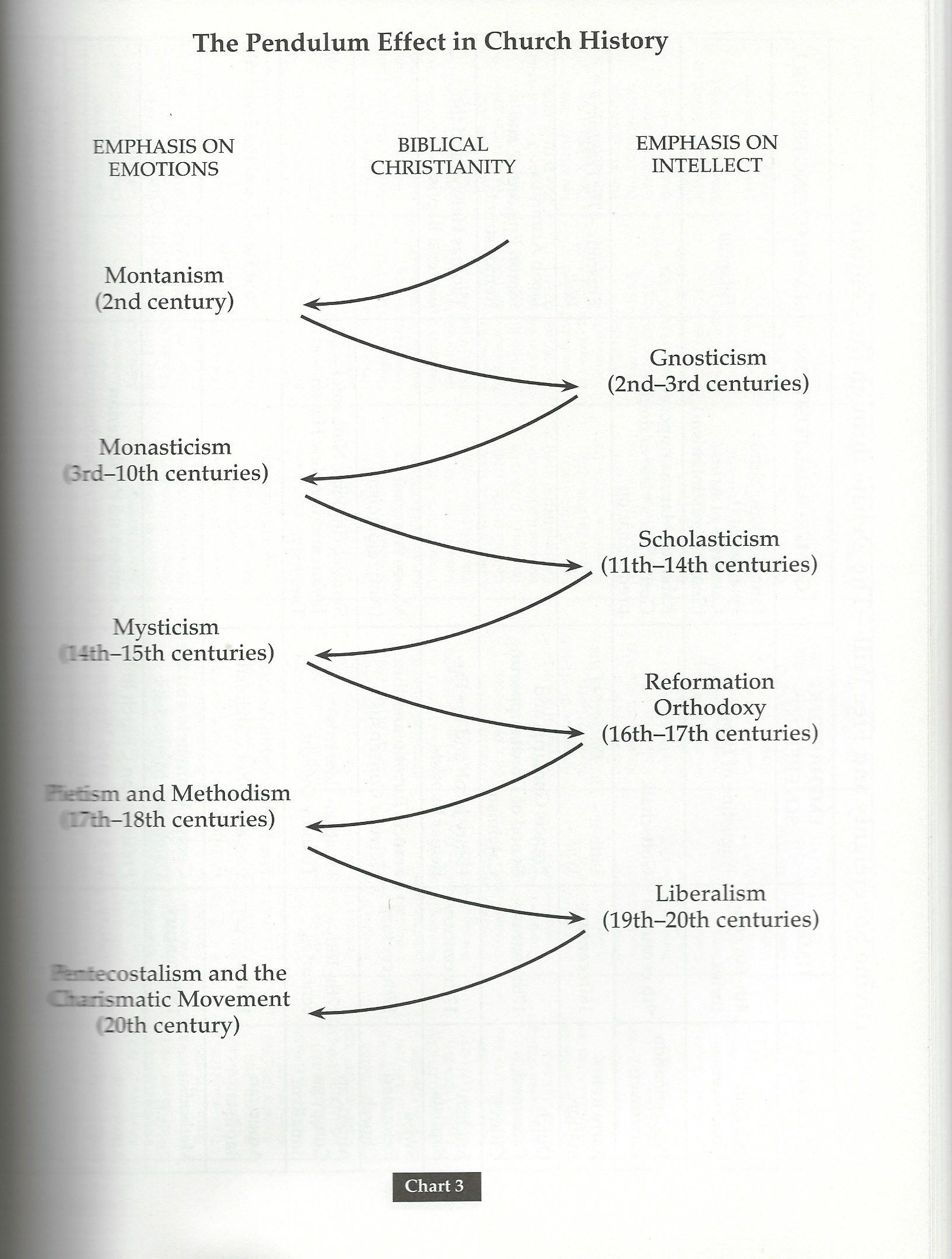

Nowhere is the need for balance more clearly seen than in Church History. Twenty centuries give ample testimony of the difficulty of living in a balanced way for Christ. In fact, one teacher has organized a study of Church History by following what he calls “the pendulum effect” as it goes from extreme intellectualism on one hand to extreme emotionalism on the other (Walton, chart 3). While the chart may be overstated as to some of its details, the general pattern points to the difficulty of keeping a balanced approach to following Christ.

This study will focus on the pendulum effect and how extremes beget extremes. It will do so by examining two examples of extreme reactions found in Church History. The first example will look at the Gnostic heresy of the 2nd century and the far reaching reactions it generated. The second will be drawn from the dawn of the Reformation, looking at Martin Luther’s reaction to Medieval Catholicism in his doctrine of justification. By making such a study it is hoped that the reader will be able to avoid the pendulum effect in his or her life and offer balanced service to Christ.

2nd Century Crisis of Identity

The end of the first century witnessed many transitions in the Church: the Apostles were passing from this life; those on whom the Apostles’ had laid their hands were now growing older or passing, and persecution of Christians removed many from leadership in the Church. These transitions, coupled with the rise of heretical groups brought a serious identity crisis to the Church (Ferguson, Defining, 10).

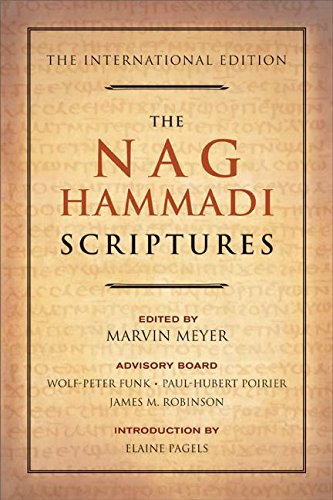

Once thought of as an heretical offshoot of Christianity, some scholars believe that Gnosticism arose prior to and independently of Christianity, but there is no unanimity in the precise origin of the several diverse groups that attached themselves to Christianity in the second-century (Scholer, 13). These groups contained a combination of Jewish, Hellenistic, and Oriental elements in their teaching and practices. Whatever their origins, Gnostics found Christianity attractive and allied with it to produce a number of second century sects. Little of the precise organization of these groups is known today. Until recently, most of what was known about Gnosticism was found in the writings of Church leaders who opposed it. But in 1945 the Nag Hammadi materials were discovered in the desert of Egypt. These papyri were written in Coptic Egyptian and furnish an insider’s look at one sect of Gnosticism. These materials were translated and published in English in 1977 (Perkins, 466).

Gnosticism receives its name from the Greek word for knowledge, gnosis. Gnostics viewed themselves as heirs of a secret revelation or wisdom given by Jesus, the Great Teacher. This knowledge is not learning in the typical sense of understanding truth through reason, but it is a “revealed knowlege” imparted through secret teachings by a heavenly messenger (Perkins, 465). Gnostics believed that man’s basic problem was ignorance, not sin. Thus, what one needs is a saving knowledge. Several groups had an elaborate division of humanity into three orders or classes. At the bottom were pagans, who were viewed as possessing only matter or bodies (Greek soma). In the middle were “ordinary” Christians who had come into possession of a soul (Greek psyche or hyle). At the highest level were the Gnostics who had been enlightened and possessed a spirit (Greek pneuma). Gnostics like Marcion at Rome, borrowed heavily from the writings of Paul, amply supplied with their own interpretations. Most Gnostic groups organized themselves on a school model and were led by a teacher. In addition to Marcion, other important second-century Gnostic leaders were Basilides of Alexandria, Egypt and Valentinus of Rome (Scholer, 13).

Fundamental to nearly all the Gnostic sects was a dualism of nature expressed in contrasts: light-darkness, truth-error, good-evil, spirit-matter. This dualism was expressed in an anthropology where man was viewed as being composed of three parts: body, soul, and spirit. Man is imprisoned in this existence which causes deep dissatisfaction and frustration. Some Gnostic groups developed elaborate myths describing man’s origin, destiny, and salvation. These Gnostics taught that salvation came by way of a heavenly messenger who descends through stellar and planetary spheres, defeating the rulers of these realms (Greek archons, see Col. 2:15). This messenger finally comes to earth to bring gnosis to man. This revelation awakens the spirit trapped inside the body. At death this spirit is freed from the body and begins to make the long journey through the imprisoning planetary and stellar regions. As the spirit passes through each sphere it is freed from the soul until it is finally absorbed into divinity.

For those who bought into this view of man, it resulted in a different Christ. Gnostics depicted Jesus as the messenger from above who came to reveal saving knowledge to men. He was the “great teacher.” This savior of mankind was a pure spirit according to the Gnostics, for otherwise he would be imprisoned in soul and body and therefore, a fellow prisoner who could not help others to escape. If it seemed (Greek, dokeo) to the disciples that Jesus was human, this was either an intentional deception or the inability of the disciples to understand a pure spirit being. Gnostics were sure that Jesus was not composed of body and soul; that he was not born of Mary; that he did not die on the cross. This different view of Christ also rejected the Old Testament and Jehovah as the God of creation. They also rejected the idea of a bodily resurrection and the second coming.

Gnostic teaching also resulted in a different ethical behavior. Because their intense dualism led them to view the material or physical world as evil and the spiritual as good, they either separated themselves from the material world in a rigid, ascetic life or they indulged themselves in physical pleasures, believing the spirit had nothing to do with the body (Gonzalez, 60). Both variations, ascetic and libertine, developed an extreme individualistic version of Christianity which minimized responsibilities to others.

It should not be overlooked that Gnosticism made an appeal to pride, especially intellectual pride. “. . . the Gnostic approach itself created different classes that placed the ones with the ‘true insight’ in a special camp superior to ordinary Christians. Intellectual elitism is a danger always for those ‘in the know’.” (Ferguson, CH, 100).

Bishop, Creed, Council: The Response to Gnosticism

The reaction to Gnosticism by mainstream Christianity or the orthodox Christians was a pendulum swing to an opposite extreme. This reaction accelerated the already developing Monarchial Bishop, the use of creeds, and meetings of Church councils (Ferguson, CH, 88). All three would have long term effects on subsequent Church history.

Emerging from the plurality of elders (bishops, presbyters, or overseers) in first century Christianity (Acts 14:23; 20:17-28; Eph. 4:11; Phil. 1:1; 1 Tim. 3:1-13; Titus 1:5-9; 1 Pet. 5:1-3), came the gradual development of the monoepiscopacy or one bishop. This bishop presided authoritatively over worship. He led worship and policed those who could take part in the weekly communion services. He was the teacher instructing would be converts in a lengthy testing period before baptism. He was viewed as holding the truth as a rightful successor to the Apostles in contrast to corrupting teachers like the Gnostics. Ignatius is one of the early “Church fathers” whose writings urge Christians to follow closely to their “bishop” in distinction from the other presbyters. "You must all follow the bishop, as Jesus Christ followed the Father, and you must follow the board of elders as you would the apostles; and revere the deacons as the command of God. Let no one do any of the things that have to do with the Church without the bishop. . . . Wherever the bishop appears, let the people be . . . It is not permissible to baptize or hold a religious meal without the bishop, but whatever he approves is also pleasing to God." (Ignatius, To the Smyrneans, 8).

Due to the doctrinal confusion of the Gnostics, brief doctrinal statements were developed to test the orthodoxy of candidates for baptism or participants in the communion. These brief statements began with the words “I believe” (Greek, pistueo; Latin credo). These “creeds” were touchstones of faith in a period in which there were no copies of the Bible for individual Christians. These statements contained practical anti-Gnostic statements which separated true believers from the Gnostics. Note the Old Roman Creed, now believed to be from the year 180 AD.

I believe in God the Father Almighty;

And in Jesus Christ His Holy Son, our Lord;

Who was born of the Holy Ghost and the Virgin Mary;

Crucified under Pontius Pilate and buried;

The third day rose again from the dead;

He ascended into heaven,

And sits at the right hand of the Father;

From there he shall come to judge the quick and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Ghost;

I believe in the Holy Church;

I believe in the forgiveness of sins;

I believe in the resurrection of the bodyl

I believe in the life everlasting (Greek version).

The multiplicity of Gnostic groups troubled Christians throughout the Roman Empire, but nowhere more so than in Asia Minor. In this region, bishops began meeting in councils or synods to deal with their common crisis. These councils affirmed the authority of the Church universal (catholic) as opposed to the individual groups of Gnostics. In addition, these meetings helped to push the understanding that revelation from God was finished and the canon of Scripture was closed (Perkins, 468).

The second century crisis of identity brought about a separation of Gnosticism from mainstream Christianity, even though Gnosticism’s influence would continue to be felt for another three centuries (Perkins, 469). The response of mainstream Christianity however, was a reactionary pendulum swing which sowed seeds of departures from New Testament Christianity. Bishops, creeds, and councils would have long term effect on that which was viewed as authoritative in doctrine and practice among those professing to follow Christ.

Martin Luther and Justification from Sin

In the early 16th century a young Augustinian monk was troubled about his soul. He found no relief in the sacramental practices of Medieval Catholicism and the confessional booth. No assurances from his abbot relieved him. A trip to Rome only brought further doubts of a system that seemed to revolve around “works” salvation in the form of acts of penitence rather than real repentance and change of life. This young monk confessed: "I was a good monk and I kept the rule of my order so strictly that I may say; that if ever a monk got to heaven by his monkery, it was I. All my brothers in the monastery who knew me will bear this out. If I had kept on any longer I should have killed myself with vigils, prayers, reading, and other work." (Bainton, 34). Thus began Martin Luther’s spiritual journey which culminated in the Protestant Reformation.

Luther’s turmoil about his salvation began with original sin, after all he was an Augustinian monk, reading his Bible through Augustine’s glasses. It was compounded by a distorted view of God. Looking back on this time in his life he wrote: "I did not love, yes, I hated the righteous God who punishes sinners, and secretly, if not blasphemously, certainly murmuring greatly, I was angry with God, and said, “As if indeed, it is not enough, that miserable sinners, eternally lost through original sin, are crushed by every kind of calamity by the law of the decalogue, without having God add pain to pain by the gospel and also by the gospel threatening us with his righteousness and wrath!” (Luther, 21).

Up to this point in his life, Luther had viewed God’s righteousness as only a judgmental hammer waiting to fall on sinners. But Luther began to change as he studied the Bible, particularly, Psalms and Romans. Two key verses for him were Psalm 71:2: “Deliver me in your righteousness and cause me to escape; incline your ear to me, and save me!” and Romans 1:17: “For in it [the gospel] the righteousness of God is revealed from faith to faith, as it is written, ‘the just shall live by faith’.” With this discovery of the righteousness of God as deliverance through the gospel rather than judgment, Luther’s hatred toward God was transformed into love. From this point on in his life, Luther viewed salvation as entirely in the hands of God. He viewed the function of the law and the Old Testament as driving the sinner to God’s grace in the gospel. This grace was appropriated by faith and not granted by the Catholic church, sacraments, or surplus merits of the saints through the sale of indulgences. In reaction to the Catholicism he had experienced, Luther proclaimed justification by faith alone (sola fidei). In his translation of the Bible into his native German, Luther changed Romans 3:28 from “justification by faith” to “justification by faith alone” (Bainton, 261). Since the epistle of James states, “You see then that a man is justified by works and not by faith only”(Jas. 2:24), it is not surprising that Luther condemned the epistle as being “full of straw” (Luther, 19). The pendulum had once again swung past the middle to the opposite extreme.

For By Grace You Have Been Saved Through Faith

Christians need to know the joy and assurance of salvation without the torment of “have I done enough to be saved?” Ephesians 2:8-10 teaches the proper relationship of grace, faith and works without passing to the extremes of faith alone or works salvation. "For by grace you have been saved through faith, and that not of yourselves, it is the gift of God, not of works, let anyone should boast. For we are His workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them."

Salvation is God’s gift. It is found in God’s initiative of love (1 John 4:19). There is no one who merits this favor; no one who could work enough to deserve it. Paul consistently uses the language of grace in this passage. Salvation is a gift. There can be no boasting on man’s part. We are His workmanship, first in creation, then in salvation.

God has created humans not machines. As such we have been endowed with the freedom to love, to worship, or to sin. God offers his gracious gift, but it must be received by faith. God’s will does not override the free will of man. For example, a man by his will takes a woman to be his bride, but not without her willingness in the matter! This faith or choice of the will is the response of love to the love of God. It is expressed in obedience to what God has asked men to do in faith (Acts 2:37-38; Acts 9:6; Acts 22:16; Acts 10:6, 33; Acts 11:14; Acts 16:30-34). It is to proceed in full assurance that what God has promised, He will perform (Rom. 4:21). To respond in obedience does not nullify grace or faith! It is not legalism to preach that men of faith obey what God aks them to do.

God’s purpose for His new creatures in Christ is that they will practice good works. This is the Christian walk or life conduct. It is to walk in the light with full joy and assurance, knowing that God’s salvation has provisions for children when they fall (1 John 2:1-6). The welcome of heaven is “well done, good and faithful servant” (Matt. 25:21, 23).

The salvation which is by grace through faith is illustrated in the lives of the heroes of faith as found in Hebrews 11. This chapter treats equally Abraham, father of the faithful, but also Rahab the harlot. They both trusted in the grace of God, and both expressed that trust in obedience. In particular, note the case of Noah. Noah “found grace in the eyes of the Lord” (Gen. 6:3). By faith he “prepared an ark for the saving of his household” (Heb. 11:7). Did Noah say, “I am saving myself, by building this boat by my design and knowledge”? Did Noah say, “What drudgery and a burden salvation is as I work building this boat”? Did Noah get on board, doubting if he had done enough to make the boat float? Obviously, the answer is no to all of these questions! Because of this, Noah is an example for Christian salvation, “There is also an antitype which now saves us – baptism (not the removal of the filth of the flesh, but the answer of a good conscience toward God), through the resurrection of Jesus Christ.” (1 Pet. 3:21). Salvation is by grace through faith.

Applying This Study

Balance is extremely difficult to achieve in life, and especially in one’s life in Christ. Perhaps the meaning of Christian maturity (Eph. 4:15) is to be able to walk without swinging to extremes. Gnosticism should warn all Christians of the dangers of pride, especially intellectual pride. But departures from God’s design, no matter how well intentioned, only bring more difficulty. One wrong does not justify another.

All individuals should take the matter of their salvation as seriously as Luther. Full assurance and joy in salvation is not found in a surplus and deficit, check book view of religion, but in full knowledge of the One who died for us and in our obedience to His commands, as in the example of the Ethiopian nobleman (Acts 8:35-40). But let us avoid the extreme reaction of Luther to a works religion. Obedience to the revealed will of Christ is the balance between the extremes of works and faith only. ". . . the Spirit of Christ is one that excludes all turning from or neglect of the commands of God, or substitution of other service for that ordained by God, and insists on rigid obedience to the divine will as the only fulfilling of love and the only means of union with God and of cleansing of sin by the blood of Christ." (Lipscomb, 281).

Works Cited

Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand - A Life of Martin Luther. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950.

Ferguson, Everett. Church History, vol. 1. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing, 2005.

______________. “Defining the Faith,” Christian History & Biography 96 (Fall 2007):8-11.

Gonzalez, Justo L. The Story of Christianity, vol. 1. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1984.

Ignatius. “Letter to the Smyrneans,” in The Apostolic Fathers, Edgar Goodspeed, trans. New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1950: 228-232.

Lipscomb, David. Salvation from Sin. J. W. Shepherd, ed. Nashville: The McQuiddy Printing Co., 1913.

Luther, Martin. Selections from His Writings, John Dillenberger, ed. New York: Anchor Books, 1962.

Perkins, Pheme. “Gnosticism,” in Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, vol. 1, 2nd ed. Everett Ferguson, ed. New York: Garland Publishing, 1997:465-470.

Scholer, David M. “In the Know,” Christian History & Biography 96 (Fall 2007): 12-17.

Walton, Robert C. Chronological and Background Charts of Church History, rev. ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing, 2005.

Wedin, Michael V. “Aristotle” in Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Robert Audi, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995:38-45.