Spiritual Revival

by Bruce Daugherty

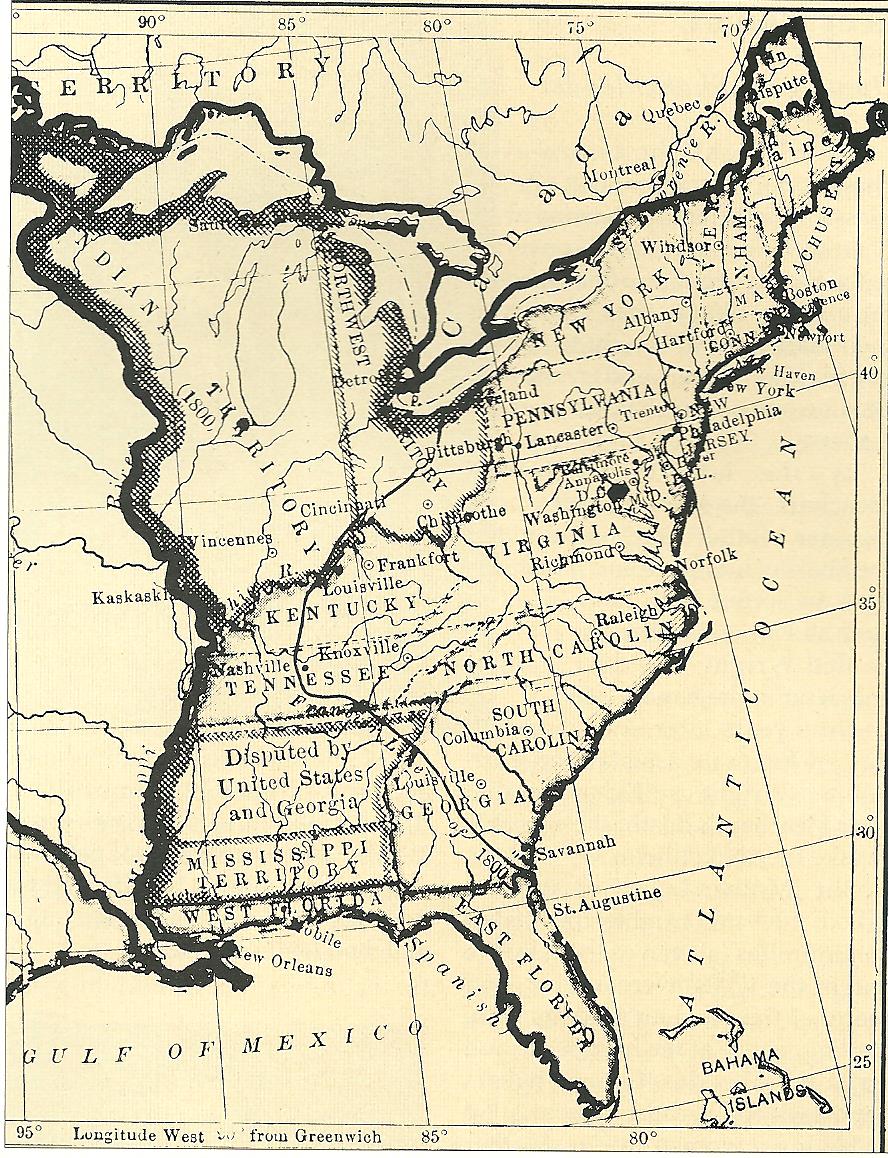

In Church History studies it is known as the 2nd Great Awakening. Because this “awakening” included the Cane Ridge Revival led by Barton W. Stone, it should be studied by those interested in Restoration History, especially to those who are interested in the events centered in the Ohio Valley. While the 2nd Great Awakening included revivals in the Eastern states, this study will concentrate primarily on the events that took place in Kentucky. It also seeks to share some observations on similarities and important differences between that time and ours.

The First Great Awakening was an emotional response to the formalism and spiritual indifference among the denominations established in the English colonies. In several ways, this paralleled the Pietism movement in Europe and England. (Cross & Livingstone, 702). This revival rose among the Dutch Reformed Churches through the efforts of Theodore Frelinghuysen. (Nutt, 85). It then spread to the Presbyterians and Congregationalists through the preaching of Jonathan Edwards and George Whitfield. (Cross & Livingstone, ibid.). The years of 1739 - 1750 saw a great response to preaching that was directed more to the emotions, though not neglecting the intellect. Emphasis was placed on an individual’s response to God resulting in conversion. While this is accepted as matter of fact today among evangelicals and others, this was a radical departure from the strict Calvinism of the day. (Noll and Lang, 9-10). Stress was also placed on having visible evidences of conversion such as fainting, screaming, crying, singing or some other physical response. Those who did not have such experiences were “denounced as unregenerate.” (Cross & Livingstone, ibid.). The results of this preaching saw a marked increase in church attendance and men studying for the ministry in schools like Yale. It also saw renewed vigor in moral living that had previously lapsed.

But the movement had its critics. Some viewed the “spiritual experiences” with disdain and believed it appealed to base, sensual emotions, rather than spiritual ones. The established churches and their clergy believed such experiences were just emotional triggers pulled by overzealous and manipulative preachers. Churches in New England and New Jersey soon divided into “Old Lights” (those opposed to revivalistic preaching) and “New Lights.” This division took on theological implications as well, as clergy and members alike debated the departures from Calvinism in favor of “experimental faith.”

By 1750 the wave of spiritual emphasis was subsiding as pressing matters of politics took hold of the minds and emotions of those living in the colonies. The struggle for the New World resulted in the French and Indian War (1754-1763), which left the British in control of the eastern half of North America. But colonial desires for independence challenged the institutions of authority of the victors: Crown, Courthouse, and Church (Anglican). The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) brought the desired freedom and changed forever the religious landscape of the new country. The Anglican Church or Episcopalian was relegated to secondary status while Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches rose in popularity.

Spiritual Crisis

For religious minded people, the waning years of the 18th century seemed to be ones of spiritual decline. In New England, the President of Yale, Timothy Dwight grew concerned over the growth of infidelity among his students.(Nutt, 86). This “infidelity” was due to fondness for the ideas of French Enlightenment and influenced by the deism of Americans like Tom Paine and Ethan Allen. In the South, the threat was perceived as more from apathy than infidelity. Drury Lacy, a veteran minister and teacher at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia described the conditions: “The dry fields and languishing vines, exhibit a too striking picture of the present State of the Church. Refreshing showers and fruitful seasons have been restrained, both in the fields and the Assemblies. We but seldom have the pleasure to see persons deeply affected, and tears streaming from their eyes. The harvest seems to be past. God has called his Labourers out of this part of His vineyard, and I am left here like an old servant upon a desolate farm. I go around once in a while to keep up the fences; and in good weather I try to thresh a little. But I have so many complaints & lazy to boot, that very little is done.” (Boles, 1787, 12).

A British traveler making his way across Virginia in 1796 left this description of the religious conditions: “. . . the people have scarcely any sense of religion, and in the country parts, the churches are falling into decay. As I rode along, I scarcely observed one that was not in ruinous condition, with the windows broken, and doors dropping off the hinges, and lying open to the pigs and cattle wandering about the woods.” (Boles, ibid., 14).

There were many factors contributing to this spiritual decline. For a time, people had to focus on the simple task of rebuilding in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War. Homes and farms needed to be rebuilt after years of war, destruction, and neglect. In essence, secular matters took priority over the sacred. And as material prosperity was gained, many people were lax in returning the priority to the spiritual side of life. It was a repetition of the situation after Israel returned from the Babylonian captivity. “Is it time for you yourselves to live in your paneled houses, and this temple to lie in ruins?” (Haggai 1:4).

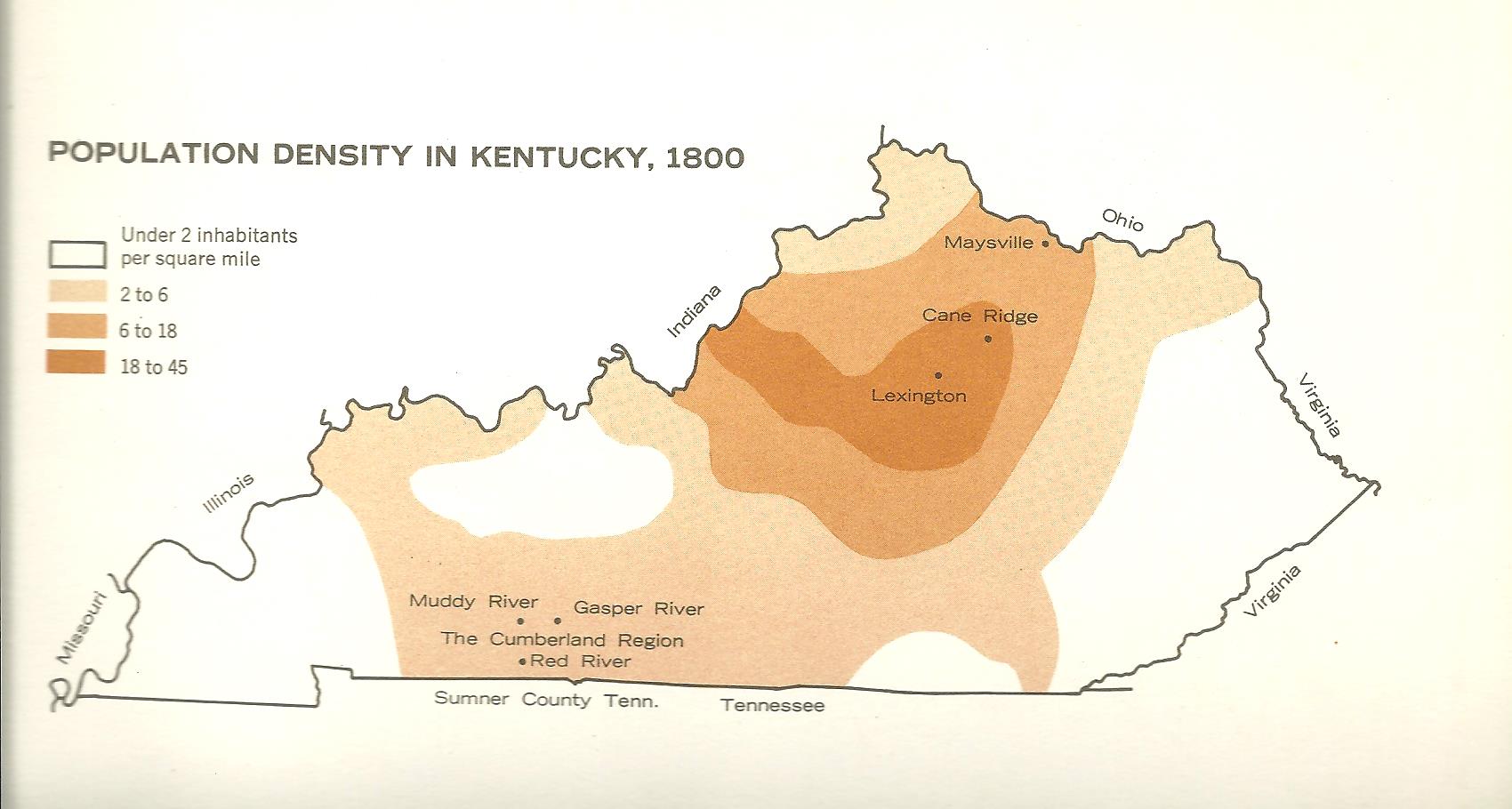

Migration to the West also contributed to the diminished following of religion. This emigration from the established churches in the East left many of the churches weakened in numbers and morale. Even the more religiously inclined who arrived on the frontier, gave priority to clearing land, building cabins, and making the land fit for farming. Religion, as well as education, would have to come later.

Deism also figured in the religious decline. While infidelity was never as great a factor as indifference, the threat from deism was genuine. Deistic pamphlets, books and papers circulated. Clubs and secular societies were formed. Men like Ethan Allen went on speaking tours and gained a following. The activities of deists “were almost entirely confined to New England and the Middle Atlantic states, but their reputations penetrated to every corner of the young nation.” (Boles, ibid., 21).

In addition, the Western increase in population outdistanced the churches’ ability to keep up with the needs of the pioneers. There simply were not enough established churches and trained religious leaders available on the frontier. Though Bible readings in home devotionals were staples for the pioneers, the longing for real spiritual feeding, the absence of participating in communion services, the absence of ordained men to officiate at rituals like baptisms, weddings, and funerals all contributed to the spiritual malaise.

Theology of Revival

While a mood of pessimism about Christianity hung over the minds and hearts of many leaders and members of the denominations, there were signs that something could reverse the situation. Slow but steady conditions were being created that would throw off the dormancy of spiritual feelings. Though despondent, the faithful never gave over to despair.

John Boles states that a “great” awakening requires certain preconditions. He lists these as “a network of churches and ministers, at least a core of believers, and a perception that the society has fallen away from a better state of religious piety that existed sometime in the past.” (Boles, Great, 311). The perception of spiritual decline has already been noted above. This crisis led to deep reflection on the causes of this decline. As the different factors were noted, a theological rationale was formed for understanding what had occurred and how it could be changed.

Nearly all the religious leaders of the time were Calvinists of varying degrees. One of the tenets of Calvinism is God is Sovereign. This Sovereignty places a high confidence in God’s Providence. With this theological outlook, the decline of religion was interpreted as God’s discipline on the churches for their moral lapses. But if those sins and failures were acknowledged and confessed by the faithful, God would forgive their sins and lead them to revival. “Thus the decade of doom became a season of hope, with the remnant of the faithful expecting deliverance at the end of the century. Across the region a feeling of expectancy replaced a sense of despondency.” (Boles, Great, 312).

Those trusting in God’s triumph needed to respond to the decline with fasting and prayer. This was a formula that was traced back to the Old Testament. (2 Chronicles 7:14; Nehemiah 1:4; Daniel 9:3-19). Fasting would be the outward demonstration of rejecting worldliness and repentance. “Admission of wrongdoing was the heart of repentance, and the fast was a public confession. Prayer then was needed for calling upon God for forgiveness and for spiritual aid. Fasting meant that one desired to change his way of life and was willing to serve God, not the world. The act of praying signified that one accepted the necessity of dependence on God.” (Boles, 1787, 31). A forgiving, loving Sovereign would accept the repentance of His subjects and respond to their prayers. A new age would dawn.

A secondary but related theological strand was belief that the new age to come might actually be the harbinger of the return of Christ. This was a quiet undercurrent in the stream of Calvinism, but it was present. One of the architects of the Cane Ridge revival, Richard McNemar wrote, “there would be glorious times upon earth, and Christ would appear again, and set up his kingdom, and gather the nations into it.” (Boles, ibid., 35).

A strong belief in the Sovereignty of God, trusting in His triumphant Providence, gave believers hope that a better day was at hand. Fasting and confessional prayer became an integral part of life for those who believed a loving Father would respond to His children. “Like a room filled with oil-soaked cloths, the South was primed to blaze with the fires of religious zeal. Once an outbreak occurred of sufficient intensity and size to attract more than local attention, the revival spark would sweep across the South.” (Boles, ibid., 35).

It Only Takes a Spark

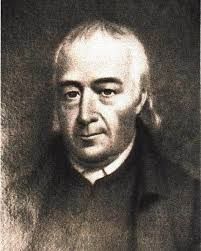

The spark began in 1798 in Logan County, Kentucky. The synchronization of men, mood, and moment touched off a wave of revival that would sweep through the South. The architect of this spark was James McGready, a Presbyterian preacher. “His ministerial accomplishments illustrate how one man, propitiously placed, could initiate a broad social movement.” (Boles, ibid., 36).

McGready had been trained for ministry in the “log college” of John McMillan in Pennsylvania. There McGready had been exposed to New Side Presbyterian beliefs that religion should be more heartfelt and that a conversion should be marked by an identifiable experience. Preaching under this type of thinking was designed to appeal more to the emotions than reason. While never abandoning his theological orientation in Calvinism, McGready proved to be an apt practioner of the new style of preaching. (Opie, 447).

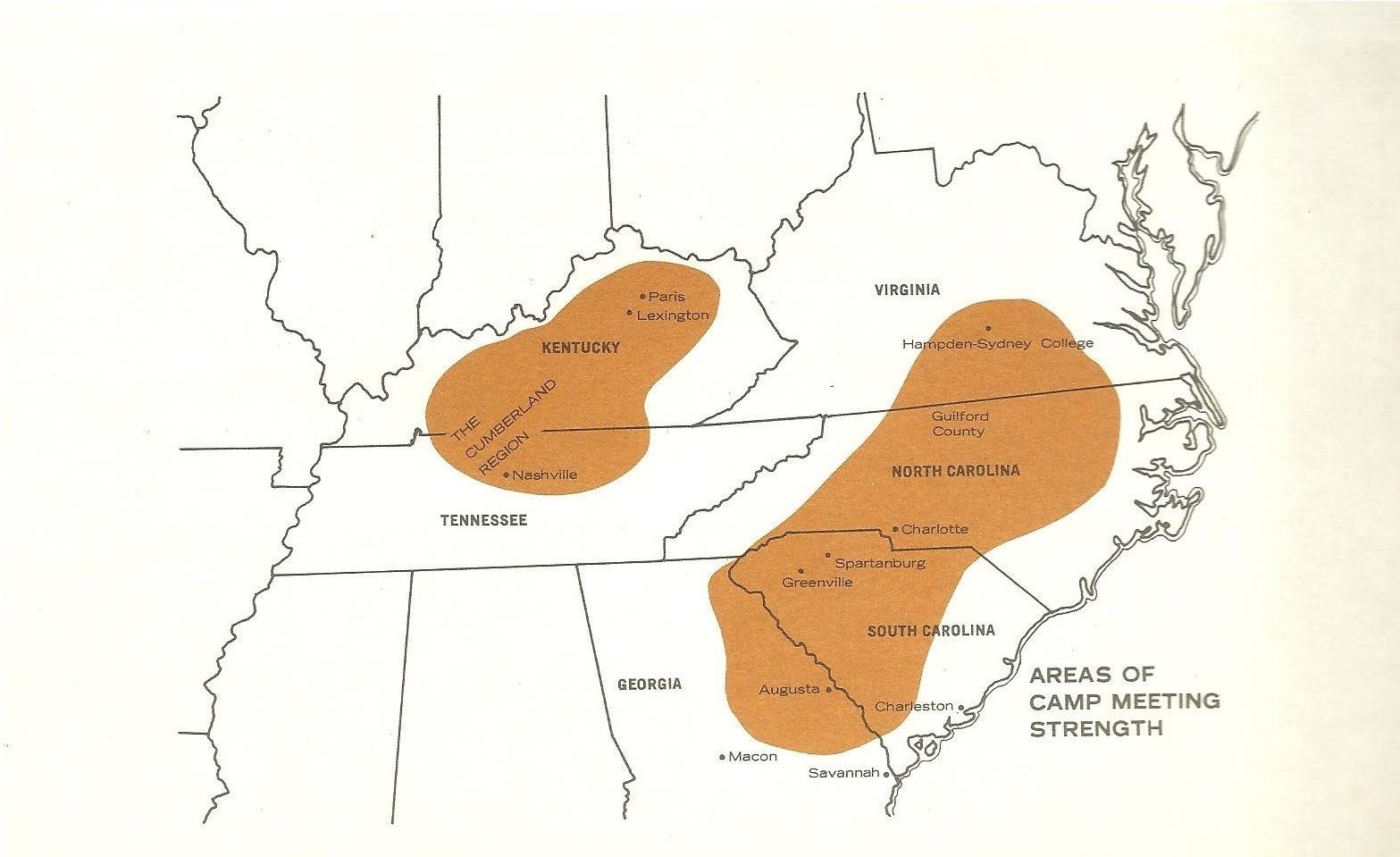

After completing his education and receiving license to preach, McGready traveled to North Carolina, stopping first in Virginia at Hampden-Sydney College which was undergoing its own wave of revival, under the effective preaching of John Blair Smith and others. (Boles, ibid., 38). After drinking deeply in that environment McCready journeyed to Guilford County, North Carolina where he began his ministry which included frequent preaching and teaching at David Caldwell’s “log college.” It was here that Barton W. Stone was trained and came under the influence of McGready. Stone described the first time he heard McCready: “Such earnestness, such zeal, such powerful persuasion, enforced by the joys of heaven and miseries of hell, I had never witnessed before. My mind was chained by him, and followed him closely in his rounds of heaven, earth, and hell with feeling indescribable. His concluding remarks were addressed to the sinner to flee the wrath to come without delay. Never before had I comparatively felt the force of truth. Such was my excitement, that, had I been standing, I should have probably sunk to the floor under the impression.” (Stone, 8).

In 1797, McGready moved to southwest Kentucky to minister to three congregations located in Logan County. “The Second Awakening revealed its true force only after it crossed the Appalachians. Its advance agent was the Presbyterian James McGready.”(Enzor, 14). Over the next four years McGready led revivals that spread throughout the region. The revivals consisted of four day camp meetings where there would be arrangements for setting up tents and campsites, provisions for sitting on long rough-hewn log benches, speaker stands, and a planned program of preaching, and inclusion of a Sunday open communion service. Attendees numbering in the thousands from all religious bodies traveled as much as hundred miles to participate in the event. Some came out of curiosity; others came with a more serious purpose, determined to present themselves and their families for promoting the cause of God and to receive a long desired re-invigoration of faith (Boles, 1787, 55). Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist preachers preached almost continuously with lessons aimed at conversion. Doctrinal differences were set aside in favor of the doctrines they shared in Calvinism: man’s total depravity and salvation by faith in Christ. “One thing that seemed especially remarkable, and was constantly singled out in the reports of this and later similar occasions, was the extent of interdenominational cooperation.” (Boles, ibid.).

But it was the response to the preaching that created the real sensation. One woman, who had long been seeking assurance of her salvation began shouting and singing. (Boles, ibid., 53). Others began crying as they sought salvation and looked for God’s deliverance. This response, unusual for the day, convinced some of the preachers that this was truly God’s working. Other meetings followed with similar responses. “ . . . instantly the divine flame spread through the whole multitude. Presently you might have seen sinners lying powerless in every part of the house, praying and crying for mercy.” (Boles, ibid., 56). These responses seemed to be the hand of God, answering the prayers of the faithful on the frontier. As the crowds grew, the meetings continued with similar emotional responses. Having never experienced these type of responses, preachers and congregants alike believed that this was an outpouring from God similar to the day of Pentecost recorded in Acts 2. And as word spread from place to place about the experiences, no one wanted to be left out of what God was doing. And so the revival spread.

Young people, who had long been ignored in the Presbyterian sacrament services, led the responses. (Boles, ibid., 44). Many of the youths who responded were the children of devout, praying parents. “Quite understandably, the impressionable, easily frightened youngsters, who by virtue of their age had never experienced a period of revivalism and mass conversion, were an easy mark for the hypnotic proselytism of the camp meeting.” (Boles, ibid., 57).

The responses to the preaching encouraged the preachers. An important observation was noted by a Virginia Baptist: “Seldom do we see a dull preacher, and a lively church, or vice versa. Therefore, for the most part, to reform the ministry, is to revive the church.” (Boles, ibid., 63). These now excited men preached more passionately and worked more tirelessly than before. Previous complaints about the decline in religion, gave way to praise for the work of God.

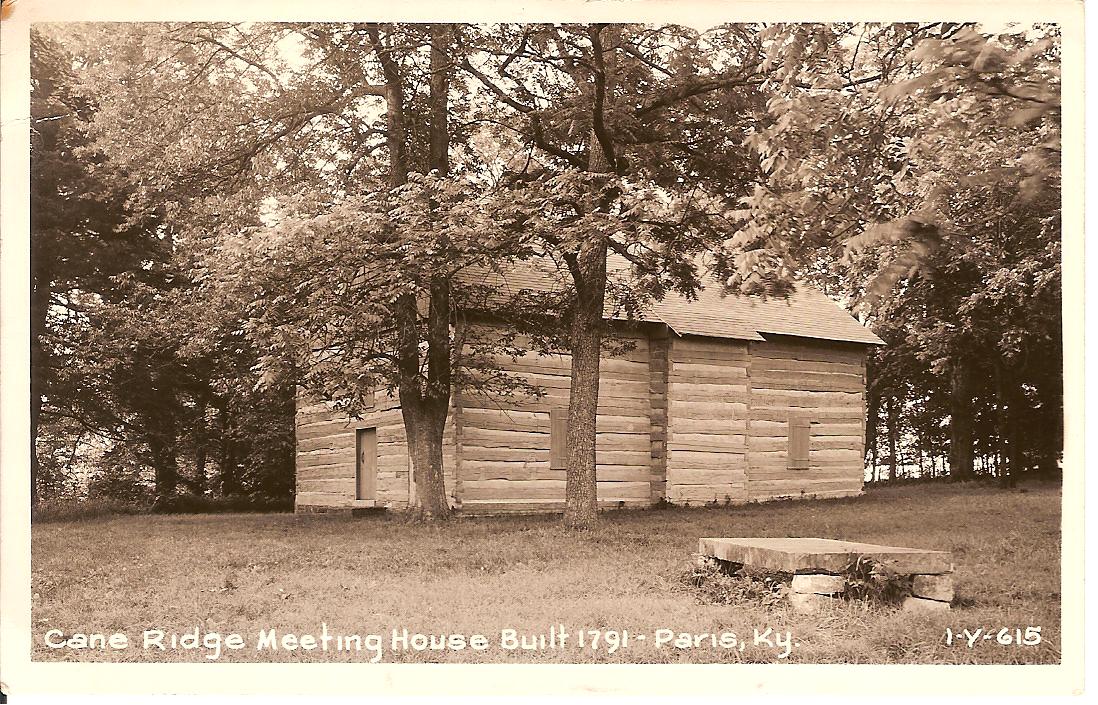

The Cane Ridge Revival

The climax of these camp meetings was the great Cane Ridge revival in August 1801. One of the architects of this camp meeting was Barton W. Stone. Stone had migrated to Kentucky in 1798 where he served the congregations of Concord and Cane Ridge located in Bourbon County, Kentucky. Stone had never been fully persuaded of the Calvinist doctrine of election. These misgivings had almost prevented him from being ordained to preach for the Presbyterians. But when examined for his orthodoxy, he proclaimed his loyalty to the Westminster Confession of Faith, “as far as I see it consistent with the word of God.” (Stone, 29).

The answer satisfied the synod that ordained him, but it meant that Stone was open to an understanding of the Bible which squarely placed him among the New Side Presbyterians. Having been already exposed to McGready’s preaching in North Carolina, Stone had also been an eye-witness to the camp meetings in Logan County in 1800. He confessed, “The scene to me was new and passing strange. It baffled description.”(Stone, 34). Despite acknowledgement of some excesses, Stone was convinced that this was a genuine work of God as he viewed the ‘slain’ rise to shout and exclaim their praise for the love of Jesus in saving them. (Stone, 35). Stone carried the news back to his Bourbon County congregations. Within minutes of hearing the report, Nathaniel Rogers and his wife, rushed out of the church, embraced Stone and began praising God in loud voices. Soon, many others in the congregation had fallen to the ground, pleading for mercy from God. Stone said, “The effects of this meeting through the country were like fire in dry stubble driven by a strong wind.” (Stone, 37). Having witnessed this reaction, Stone made preparations for a camp meeting at Cane Ridge. This was not far from Lexington and situated in the heart of Kentucky’s population boom.

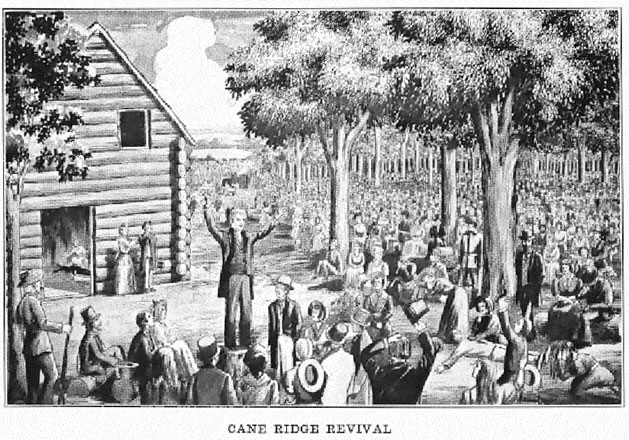

In the first part of August 1801, an estimated crowd of 15-25,000 people choked the roads and trails leading to Cane Ridge. For the next five to six days there was an unceasing cacophony as preaching, praying, singing, and emotional responses filled the air. “The noise was like the roar of Niagra. The vast sea of human beings seemed to be agitated as if by storm.” (Boles, 1787, 65). “Four or five preachers were frequently speaking at the same time, in different parts of the encampment, without confusion. The Methodist and Baptist preachers aided in the work, and all appeared cordially united in it – of one mind and one soul, and the salvation of sinners seemed to be the great object of all.” (Stone, 37-38). Theological differences were set aside in the effort to preach salvation to the masses. One preacher gave this insight into the revival sermons: “Sometimes there is in our discourses, a strange heterogeneous mixture of antinomianism, arminianism, and I may add, calvinism: calvinism, perhaps in the beginning, antinomianism in the middle, and arminianism at the end of a sermon.” (Boles, ibid,66 –fn 51).

The crowd, already in fever pitch due to the unprecedented scope of the revival and in a high state of expectancy for God to act, was easily moved by the preaching that placed them between the terrors of hell and the joys of paradise. “Everything was acting together – the size of the crowd, the noise of simultaneous sermons and hymns, assorted shouts, cries, groans, and praises, the exhaustion brought on by continual services, the summer heat – simply overwhelmed the participants with their beliefs in providential omnipotence.” (Boles, ibid, 66). For many participants, the sheer size of the meeting seemed to bear God’s stamp of approval. And when the strange responses to the preaching began to occur, many considered themselves to be witnessing the hand of God among them.

The Cane Ridge revival was marked by strange phenomena or “bodily agitations” or “exercises” as Barton Stone called them. (Stone, 38-39). Stone, while acknowledging that there were excesses and fanaticism on the part of some who responded to the preaching, nevertheless believed to his old age that the “exercises” had been sent by God to get the attention of the world. (Stone, 38 and 42). Stone listed five to six different types of behaviors, variously described as “the falling exercise, the jerks, the dancing exercise, the barking exercise, the laughing exercise, the running exercise, and the singing exercise.” (Stone, 39-42). Another firsthand account described the jerks: “Their heads would jerk back suddenly, frequently causing them to yelp, or make some other involuntary noise . . . Sometimes the head would fly every way so quickly that their features could not be recognized. I have seen their heads fly back and forward so quickly that the hair of the females would be made to crack like a carriage whip, but not very loud.” (Boles, ibid, 68).

While the “exercises” captured the most attention, the prevailing unity that transcended denominational ties made an impression on Barton Stone. He reminisced, “. . . all appeared cordially united in it - of one mind and one soul, and the salvation of sinners seemed to be the great object of all. We all engaged in singing the same songs of praise - all united in prayer - all preached the same things - free salvation urged upon by faith and repentance.” (Stone, 38). It was this unity, more than the bodily “exercises” that convinced Stone that the revival was the work of God.

Long Term Results of the Revival

The “2nd Great Awakening” did not last. Those who had opportunity to respond to revival preaching made their responses. More than 1000 conversions were reported at Cane Ridge. But doctrinal discord eroded the temporary unity brought on by the revivals. Orthodox Calvinists in both Presbyterian and Baptist fellowships rejected the appeal to free salvation offered by revivalist preachers. Only the Methodists would continue to utilize the revivals, transforming them into camp meetings that would continue throughout the century.

But the wave of spiritual revival begun in Kentucky would bring lasting changes to the country, especially to its southern region. The many people converted in the revivals were the catalysts in the formation of a mindset that has been described as evangelical and pietistic. (Boles, ibid., 183). Despite denominational differences, inhabitants of the region stretching from the Carolinas to Texas, shared an emphasis of a moral society built on a conservative interpretation of the Bible. In popular terminology it is known as the “Bible belt.” And while secular influences have made inroads, the echoes of revival are still heard in the region.

The Cane Ridge revival also set in motion a desire to return to primitive Christianity and a Christian unity that could overcome the division of denominationalism. “The Great Revival was intoxicating wine to the masses; a stumbling block to the orderly Presbyterians; foolishness to the upper strata of Kentuckians; hysteria to contemporary and present day rationalists; but to Stone, it may be likened to the release of another kind of atomic energy, disintegrating the bonds of creedal orthodoxy, and holding the promise that a new Christian order might unite the churches on the Bible for the glory of the coming Kingdom.” (W. West, 45). Though Stone’s understanding was still far from complete, he had gained a vision of Christianity set free from creeds and united on the Bible. “Cane Ridge turned Barton W. Stone away from creedalism to the Bible, and the Bible soon led to the preaching of the gospel plan of salvation.” (E. West, “The Gospel According to Cane Ridge,” 150). Stone had also come to ask “If people from differing denominations could be united during a week of revival, why could they not be united all the time?” (W. West, 46). Three years later, Stone and five other Presbyterian evangelists would issue “The Last Will and Testament of the Springfield Presbytery.” This document made an appeal to put an end to nonbiblical organizations and practices and follow that which is taught in the Bible. It was a first step in what would later be termed the Restoration movement.

The 2nd Great Awakening also contributed to the modification of Calvinism. Revival preachers were liberal Calvinists. McGready and Stone were already opposed to hyper Calvinism and its expression in the Confession of Faith where it deviated from Scripture. Departing from Calvin’s dogma that “election did not depend on faith,” McGready believed that faith was essential to please God. “Futhermore, M’Gready insisted that Scripture reading, prayer, and meditation should be used by the sinner as ‘means of Grace,’ preparatory to salvation.” (Enzor, 18-19). “There is every indication, however, that Calvinism was considerably softened at the Cane Ridge meeting.” (E. West, The Gospel, 150). But McGready never left his Calvinism, like Stone. In his personal theological wrestling to balance creed and revival, he maintained his orthodoxy with the Presbyterians. “The revivals that swept the frontier started among them [Presbyterians] but ended in dividing that church, as old-line Calvinists saw the danger to the doctrines of predestination and foreordination inherent within revivalism.” (E. West, Revivalism, 546). McGready’s religion “was experimental, but it was a controlled experiment.” (Opie, Jr., 449). His theology was always an anchor for the extremes of the revivals. “He was a revivalist and a realist; a realistic revivalist can do little else.” (Enzor, 19).

Since revival preaching emphasized personal conversion, nothing approaching a social gospel would be found in the South. Instead, the emphasis was on an individual ethical code. “Although occasionally a denomination would support an orphanage or care for a widow, there was never anything closely resembling a social gospel. The only way to cure society, it was believed, was to cure souls.” (Boles, ibid., 193).

Yet there were a few contributions to societal change. The liberation Barton W. Stone experienced in his new found personal freedom from creeds, led him to free the slaves he had inherited from his mother’s estate. Stone described his actions: “I had emancipated my slaves from a sense of right, choosing poverty with a good conscience, in preference to all the treasures of the world. This revival cut the bond of many poor slaves; and this argument speaks volumes in favor of the work. For of what avail is a religion of decency and order, without righteousness?” (Stone, 44). Though the institution of slavery in the South would never permit an abolitionist movement like that which occurred in the North, there were others who followed Stone’s example and freed their slaves.

Some Observations for Today

If frontier America needed a spiritual awakening, what about today? In the wake of terror attacks, racial tensions, and the catastrophic harvest of the wholesale embrace of alcohol, drugs, and gambling, arousal from spiritual lethargy is needed as never before. If the writings of Paine, Allen and the French atheists caused concern, how much more the dominance of secular Humanism thought entrenched in the institutions of the country? If apathy and indifference to spiritual needs was present then, how much more in a society where the fastest growing segment of the population is the non-religious?

The spiritual awakening under contemplation is not a plea for Pentecostalism. The excesses of Cane Ridge are to be avoided. To read these accounts today and to be knowledgeable of the insights of psychology, is to understand that the “exercises” can be explained by the combination of circumstances involved without having to believe that something Supernatural or Pentecostal was happening. John Rogers devoted a whole chapter at the end of his biography of Stone to provide a strong case for the fact that the “exercises” were the result of the doctrinal error of the day. “True penitents . . . have no definite criteria by which to assure themselves of pardon. They have no better evidence, than strong impressions, impulses, suggestions, feelings, or the agreement of their exercises of mind, with those of others, and thus trusting to such uncertain evidences, ‘measuring themselves by themselves and comparing themselves among themselves,’ they have no rational or scriptural assurance of pardon and by apostolic authority are pronounced unwise. Here then, in this vague, undefined, and undefinable notion of orthodoxy, where everything is left to conjecture, to impulse, to mere feeling to imagination, we have found an adequate cause of all these extravagances of which we are speaking.” (Stone, 385).

Stone, though very sentimental about the Cane Ridge encampment of 1801, nevertheless modified his views about revivalism. As he matured in his understanding of Scripture, Stone rejected Calvinism’s need for a direct operation of the Spirit to save totally depraved individuals. Stone learned to put complete emphasis on the power of the word of God to convert sinners. Earl West observed, “Stone came to object to this theory of the revivalists because it encouraged men to neglect the gospel since they believed that the words could not benefit ‘till they are made more powerful by the power of God.” (E. West, Holy Spirit, 664). The advent of the Shakers coming to Kentucky proved to be a blessing in disguise to Stone and the cause of Restoration. The more fanatical left to join the Shakers, allowing the work of Stone to become more Biblical and less emotional. (Humble, 26-27).

Revival can be accomplished without losing balance between head and heart. Conversion is not a question of heart over head, but of an informed mind guiding the zealous heart. Zeal according to knowledge guided the preachers of the Restoration movement. One of the outstanding preachers of the first half of the 20th century was T. Q. Martin. Martin’s style of preaching made appeal to the heart. He used humor when needed, but more often than not, he shared stories that moved his listeners to tears. But Martin also knew when emotions could be out of control. In extending the invitation during the last night of a gospel meeting, fifteen people responded. When shouting began over the response of a “particularly reckless young man,” Martin stopped the service and said: “Brethren, feeling is running too high. I should be glad for every unsaved man and woman under this roof to come forward tonight but sometimes excitement runs high and persons do what they wouldn’t do in a sober state of mind.” Without any further singing or exhortation, four more people responded, making a total of sixty-nine for the meeting. (Martin, 47-48).

What then, is the spiritual awakening contemplated? The formula of the 2nd Great Awakening looked back to God’s word for the way forward. “If My people who are called by My name humble themselves, and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then will I hear from heaven and will forgive their sin and heal their land.” (2 Chronicles 7:14). Prayer, confession of sins, repentance demonstrated in the turning away from worldliness, and passionate proclamation of the good news of Jesus Christ is the way for spiritual revival.

“Awake, O sleeper, and arise from the dead, and Christ will shine on you. Look carefully then how you walk, not as unwise but as wise, redeeming the time because the days are evil. Therefore do not be foolish, but understand what the will of the Lord is.” (Ephesians 5:14-17).

Works Cited

Boles, John B. “Great Revival, the” in Dictionary of Religion in the South. Samuel S. Hill, ed. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1997: 311-313.

___________. The Great Revival, 1787-1805. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1972.

Enzor, Edwin H. Jr. “The Work of James M’Gready; Frontier Revivalist,” Restoration Quarterly vol. 9 no. 1 (1966):11-20.

“Great Awakening, the,” in Dictionary of the Christian Church. F. L. Cross & E. A. Livingstone, eds. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1997: 702.

Humble, Bill. Like Fire in Dry Stubble: the Life of Barton W. Stone. Nashville: Gospel Advocate, 1991.

Lang, J. Stephen & Mark A. Noll. “Colonial New England – An Old Order, A New Awakening,” Christian History vol. 4, no. 4 (1985): 8-10, 35.

Martin, T. Q. A Brief Story of the Life, Experiences and Exhorations of T. Q. Martin. Jackson, TN: Laycook Printing, n. d.

Nutt, Rick. “Controversy in Christ: The Background and Context of Western Frontier Presbyterian Revivalism and the Movements Which Grew Out of It,” Discipliana 65 no. 3 (Fall 2005): 83-92.

Opie, John. “James McGready: Theologian of Frontier Revivalism.” Church History 34 no. 4 (December 1965): 445-456.

Stone, Barton W. and John Rogers. The Biography of Elder Barton Warren Stone. Cincinnati : James & Co., 1847.

West, Earl. “Revivalism – Cane Ridge Style,” Gospel Advocate vol. cxii no. 35 (August 27, 1970): 546,550.

_________. “The Holy Spirit at Cane Ridge,” Gospel Advocate vol. cxii no. 42 (October 15, 1970): 663-64.

_________. “The Gospel According to Cane Ridge,” Gospel Advocate vol. cxiii no. 10 (March 15, 1971): 149-150.

West, William Garrett. Barton Warren Stone: Early American Advocate of Christian Unity. Nashville: The Disciples of Christ Historical Society, 1954.