WE HAVE BEEN HERE BEFORE

By Bruce E. Daugherty

The coronavirus epidemic is something new for everyone. Nothing like this has occurred in our lifetimes. Since it is a new experience and with all the media hype, it is uncertain as to how to respond. The desire is to be prudent but at the same time not give oneself over to panic. We want to live by faith rather than fear.

Though we have not lived through a pandemic, there are precedents in history that can help give guidance as to what course of action individual Christians or congregations should take. One reason for studying Church history and the history of the Restoration movement is to be reminded that “there is nothing new under the sun.” – Ecclesiastes 1:9-10. Examining the responses of God’s people in previous times of pestilence and plague can prove to be beneficial to God’s people today. This article will briefly examine the responses given to the “Black Death” of 1348, Martin Luther’s course of action during the plague, David Lipscomb’s example during the cholera epidemic in Nashville in 1873, and the impact of the Spanish flu of 1918-1919 on some Christians in the Ohio Valley.

“The Black Death”

Medieval history tells of the “Black Death,” which today is believed to have been the bubonic plague, which swept over Europe in 1347-1348, and in successive waves in 1361, 1368, 1375, 1382, 1438-1439, 1454-65 and possibly 1471. The disease was transmitted by fleas and rats and thrived in the filthy living conditions of the time. Since medicine of the day was powerless to diagnose the illness, no remedy was available except preventative measures of isolation and quarantine. Though it is impossible to know exactly how many died, the mortality rate in England approached 50%, and is indicative of what was happening on the European continent. (Coulton, 131-132). The suddenness and helplessness of the situation loosened all social ties and brought out the best and worst of humanity, as many people helped their neighbors while others fled for safety to less populated areas. Many people of the day attributed the disease to a punishment sent from God on the sinfulness of the age. It went along with overall medieval perceptions that mankind was going from bad to worse.

As the plague advanced in England, parish priests suffered a mortality rate of more than 40% while the hierarchy of bishops, archbishops and cardinals suffered a mortality rate of less than 18%. These numbers indicate that many of the hierarchy had abandoned their cities and stayed in comparative safety in secluded country homes. As a result of the high mortality rates among the parish priests and a mass of resignations due to fear or an impoverishment of living due to non-support, many English churches were abandoned to birds and beasts and were rapidly going to ruin. (Coulton, 133). English bishops complained that they could not find enough priests to visit the sick, administer the sacraments and care for church property.

Due to the shortage of priests, English bishops began allowing people to confess to laypeople, especially in situations of last rites. If the penitent survived, he or she was expected to repeat his confession later to a priest. If no priest was available to administer extreme unction, then “faith in the Sacrament would suffice.” (Coulton, 130). Here were seeds of the coming religious revolution in the Reformation as the ideas of sola fide and the priesthood of all believers were already being practiced.

Another consequence of the “Black Death” was the rapid growth of the Lollards, the disciples of Wyclif. Since many priests and much of the hierarchy had fled the plague, public opinion judged them as having fallen from their sacred offices. The pretentious claims to nearly superhuman powers were negated by their conduct during the plague. The English people judged them as being unworthy of the privileges they enjoyed. The pandemic swept away the terrible “system of putting ignorant boys into the best livings, while curates at starvation wages did the actual work.” (Coulton, 138).

Luther’s response to the Plague

“Whether one may flee from a Deadly Plague” – a letter written to Dr. John Hess.

“I shall ask God mercifully to protect us. Then I shall fumigate, help purify the air, administer medicine and take it. I shall avoid places and persons where my presence is not needed in order not to become contaminated and thus perchance inflict and pollute others and so cause their death as a result of my negligence. If God should wish to take me, he will surely find me and I have done what he has expected of me and so I am not responsible for my own death or the death of others. If my neighbor needs me however, I shall not avoid place or person but will freely go as stated above. See this is such God fearing faith because it is neither brash nor fool hardy and does not tempt God.” – Luther’s Work Vol. 43:132, as cited in The Jenkins Institute, 3-16-2020.

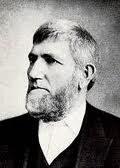

David Lipscomb’s Example in a Cholera epidemic

In the summer of 1873 the city of Nashville, like many cities of the day, experienced a severe outbreak of cholera. There were 1000 known deaths, yet historians believe that there were many more as poor people, especially former slaves, were often buried in shallow, unmarked graves with no record of their identity.

David Lipscomb wrote of the situation in several editorials in the Gospel Advocate during the months of May through August. These editorials urged Christians give help and aid to those in need, no matter the color of their skin. Lipscomb chided his fellow citizens as they fled the city to live in a safer environment in the country. He asked, “What would Christ have done? Would He have panicked and run?” Lipscomb acknowledged that prudence was needed, and that women, children, and especially the elderly ought to move to safety. But he also believed that able bodied men should remain in the city to give help to the sick and dying. Lipscomb went on to praise doctors and preachers who remained in the city when others had fled.

Lipscomb cited Matthew 25:31-46, as proof of a Christian’s duty, even in a time of epidemic. If one could not help personally, then he or she ought to make generous gifts to help the poor. When one reader criticized Lipscomb for making himself an object of charity, Lipscomb replied, “My purse is in a perfect state of collapse, as if it had the cholera . . .” Any funds he raised went to give aid to cholera victims. Lipscomb offered his critic this remedy. “A good generous gift to the poor, in the name of Christ, would relieve your soul of its bitter bile and you would feel better, much better.”

And David Lipscomb practiced what he preached. He went to the poor areas of Nashville, black and white. He fed those who were starving. He nursed and administered medicine to those who were ill. He cleaned away filth, rubbish and trash. He buried the dead. (Hooper, Call, 48-49).

Some readers were not happy that Lipscomb was helping blacks as well as whites. A Mr. Payne wrote stating that Negroes did not have souls, and therefore they were not in need of aid. Lipscomb could barely hold back his anger as he replied, “If Mr. Payne would put himself under my guidance for one week, if he possessed any honesty of heart, I would convince him of his error. How would I do it? . . . Simply by putting him to feeding and nursing starving, sick and dying Negroes.” (Hooper, Call, 50).

Lipscomb paid a price for his service. He himself contracted cholera that summer. For two days his life hung in the balance. Lipscomb eventually pulled through, but for the rest of his life he would suffer on occasions with asthma and bleeding of the lungs. (Hooper, Crying, 135-136). But Lipscomb later looked back on his activity that summer and recalled that those events were more satisfying than any one thing he had done.

Experiences of Christians in the Ohio Valley During the Spanish Flu 1918-1919

The worst pandemic in recent history is the Spanish flu of 1918-1919. It resulted in an estimated 50 million deaths worldwide and 675,000 in the United States. (CDC website, “Spanish Flu,” accessed 3-16-2020). Children under the age of five were especially susceptible and a high mortality rate ran among those aged 20-40, as well as those over age 65.

“No effective prevention existed. The medical advances necessary to isolate the virus and develop a vaccine would not occur for another fifteen years. The flu epidemic at the end of 1918 seemed a devastating throwback to the plagues of the Middle Ages . . .” (Cooper, 320).

Like pestilence and plagues of the ancient world and the medieval era, only preventative measures stopped the spread of the disease. Isolation, quarantine, the practice of good personal hygiene, the use of disinfectants, and limitations of public gatherings were the responses to the epidemic.

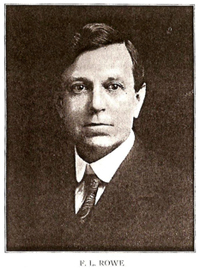

All of these measures had an impact on churches and preachers. As health officials suggested the closing of all public meetings to prevent the spread of the virus, the first reaction of many Christians was to keep attending the assemblies. Fred Rowe, owner of the Christian Leader gave this response to an inquiry from a reader in Glasgow, Kentucky, whose elderly parents were advising them to stay at home.

“By all means attend the worship. If the state authorities close the meetinghouses, you can meet in small groups in your homes, but if the meeting house is open, that is the place to go. I have never known a person to be harmed by obeying any of the commands of the Lord, so I answer this sister by saying emphatically, attend the church worship as your duty to the God of heaven.” (Rowe, 5). Rowe went on to state that he was astonished that the authorities were shutting down church gatherings. He believed they should be calling on God-fearing people to gather in prayer rather than close the doors of churches.

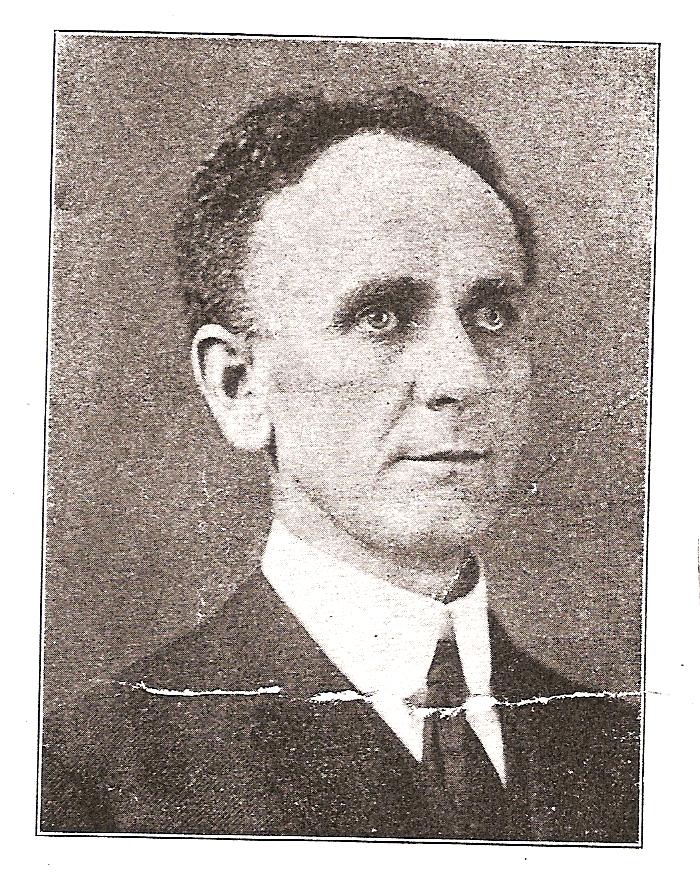

D. J. Poynter also shared his convictions about closing down the assemblies. He said that he wanted to “enter a solemn protest against closing the churches.” Poynter listed his reasons. First, he doubted whether the quarantine did any good, since he knew of individuals who worked in solitude and still came down with the flu. But while he did concede the point that it was best not to congregate, he believed church assemblies had a different character than other public gatherings. “Only well people attend, as even the slightest headache is excuse enough to stay away from the house of God. Those who attend are clean, having taken a bath and put on their clean clothes. The house of worship is clean. The assemblage lasts but a short time. The minds of the worshipers are taken away from earthly troubles, so that the effect is beneficial to their bodies.” (Poynter, 1). Poynter went on to say that if ever there was a time where men needed to humble themselves in God’s house and call on Him in prayer it was now. Though he had respect for the “learned men” he would rather trust in God and obey Him in fighting the flu.

Despite these initial reactions, many congregations in the Ohio Valley had to suspend assemblies for a six to eight week period by orders from state and local governments. Ira Moore, an editor of the Christian Leader spoke of his situation. “I have done but little preaching since Oct. 6th, when the “flu” ban was put on.”(Moore, 4). Some churches, especially small country congregations, continued to meet. Attendance numbers were low and protracted gospel meetings were canceled.

Church practices were also changed by the epidemic. In that era, many, if not all the congregations in the Ohio valley used one cup for the Lord’s supper. But as the influenza epidemic spread, practices had to adapt. In 1918 the governor of the state of West Virginia ordered all people sharing drinking vessels to have their own individual cups. This was directed towards railroad gangs and logging crews who shared a common water cooler on the job and everyone drank from the same metal dipper or cup. But the new law also included churches. Ira Moore, who had long argued for better hygiene habits from Christians, like giving up smoking and chewing tobacco, endorsed this new law and helped brethren to see that it was the contents of the cup, rather than the container itself, which was of importance in keeping the Lord’s supper.

The impact on preachers was especially hard felt. Most preachers of that era in churches of Christ were not located and they had no fixed salaries. They were itinerant evangelists who were paid as they held protracted meetings or preached for various congregations from Sunday to Sunday. When churches closed, preachers received no income. Thad Hutson spoke of his situation during the epidemic:

“I am anxiously waiting for the flu epidemic to abate so I can get back to the work of preaching the gospel. But I intend to work with my hands as opportunity allows until that time comes. I ask for the prayers of God’s people.” (Considerations, 8).

Another Ohio Valley preacher was J. H. Pennell. Pennell had helped to establish the church meeting in Zanesville, Ohio and evangelized up and down the Muskingum River valley to small country congregations as well as congregations in towns and cities. But in the winter of 1918-1919, he reported that he and his family were on a “7 week vacation.” The “vacation” was imposed because he and his family were quarantined. As a result, Pennell had no income for seven weeks. Despite the dire straits, Pennell kept his faith. His report concluded, “But the Lord will provide. No prospects for getting out soon.” (Field Reports, 12).

Many Ohio Valley homes paid the ultimate price during the epidemic. “More doughboys fell to the flu than to enemy bullets, and thousands of the wounded died because they were weakened by the disease.” (Cooper, 320). Two Christian young men from Ohio, drafted into the military, died from influenza. Edgar Callicoat of Lawrence county Ohio was called up to serve on September 4 and died a month later of Spanish flu in Camp Sherman, Ohio. (Obituary, 18). Hobart Morrison, of Harrietsville, Ohio also died from the influenza.

The home of A. A. Bunner was draped in black crepe during the fall and winter of 1918. Bunner was an evangelist from Marion county, West Virginia, but was living in Cleveland, Ohio where he was establishing a new congregation. In November 1918, Bunner reported the death of his youngest son, Laurence, aged 18. Laurence had graduated high school in the spring and had just begun his college studies at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Bunner reported, “While we feel we have sustained a great loss, our loss is his gain. Pray for us.” (Obituary, 13). Three months later, sorrow was added to the Bunner family as they were bereaved of a second son. “With a heart filled with sadness I must tell I lost another son – Rawlins Harding Bunner, aged thirty-three years. He leaves a wife and three small children. Rawlins had developed into a strong and useful preacher of the Word. Bro. Hendershot will prepare a suitable notice for the C. L. The Father knows best. Remember us in your prayers. In hope.” (A Second Son, 9). Countless other Christians suffered loss in the period, but these cited give an indication of the heartache suffered by good people during the epidemic.

Selecting Courses of Action

In light of the examination that has been made from these precedents from history, what course of action should Christians pursue today? Whether an epidemic is raging or not, ways to serve and be our brother’s keeper should be a priority. “For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.” (Mark 10:45). A spirit of faith, rather than fear will energize Christians. “For God has not given us a spirit of fear, but of power and of love, and of a sound mind.” (2 Timothy 1:7). Certainly, everyone at this time should take sensible precautions without falling into paralysis. Compassion for those in need must be a part of how God’s people respond in this crisis.

“By this we know love, because He laid down His life for us. And we also ought to lay down our lives for the brethren. But whoever has this world’s goods, and sees his brother in need, and shuts up his heart from him, how does the love of God abide in him? My little children, let us not love in word, or in tongue, but in deed and in truth.” (1 John 3:16-18).

Times like these inevitably will produce friction, even among good people. Not everyone has the same comfort level and course of action. Rather than criticize and judge others, peace and harmony must prevail among the heirs of heaven. “Be of the same mind toward one another. Do not set your mind on high things, but associate with the humble. Do not be wise in your own opinion. Repay no one evil for evil. Have regard for good things in the sight of all men. If it is possible, as much as depends on you, live peaceably with all men.” (Romans 12:16-18).

Let’s be ready to share love and gospel message with others in this time. This pandemic may cause people to awaken to their spiritual condition and their need for Christ. There will be opportunities to share faith. “But sanctify the Lord God in your hearts, and always be ready to give a defense to everyone who asks you a reason for the hope that is in you, with meekness and fear.” (1 Peter 3:15).

We must also be prepared for the inevitability that some of will suffer loss in this epidemic. May all of God’s people weep with those who weep and bind up the wounds of those who suffer.

While things look bad now, I am firmly convinced that good will come out of this. God is greater than any pandemic. I am already seeing good things being done as people make the Church a reality that is not tied to a building, but manifested in the lives of people.

It is easy to talk about Christianity when things are going well. It is another thing when we find ourselves in the storm and faith is being tested. No matter what may come the need is to persevere in doing what is right!

The example of Epaphroditis, while in a different situation, ought to inspire all of us to greater expressions of our faith. “Yet I considered it necessary to send to you Epaphroditus, my brother, fellow worker, and fellow soldier, but your messenger and the one who ministered to my need; since he was longing for you all, and was distressed because you had heard that he was sick. For indeed he was sick almost unto death; but God had mercy on him, and not only on him but on me also, lest I should have sorrow upon sorrow. Therefore I sent him the more eagerly, that when you see him again you may rejoice, and I may be less sorrowful. Receive him therefore in the Lord with all gladness, and hold such men in esteem; because for the workd of Christ, he came close to death, not regarding his life, to supply what was lacking in your service toward me.” (Philippians 2:25-30).

Works Cited

Bunner, A. A. “Obituary,” Christian Leader vol. 32 no. 47 Nov. 19, 1918:13.

___________. “A Second Son Dies,” Christian Leader vol. 33 no. 2 Jan. 14, 1919: 9.

Cooper, John Milton, Jr. Pivotal Decades – The United States, 1900-1920. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1990.

Coulton, G. G. Medieval Panorama, vol. II – The Horizons of Thought. London: Collins Press, Fontana Library edition, 1961 reprint of 1938 edition.

Hooper, Robert. A Call to Remember - Chapters in Nashville Restoration History. Nashville: Gospel Advocate Company, 1977.

_____________. Crying in the Wilderness; A Biography of David Lipscomb. Nashville: David Lipscomb College, 1979.

Hutson, Thad. “Considerations,” Christian Leader vol. 32 no. 50 Dec. 10, 1918:8.

Moore, Ira. “The Christian’s Obligation,” Christian Leader, vol. 32 no. 52 Dec. 24, 1918: 4.

“Obituary – Callicoat,” Christian Leader vol. 32 no. 43 Oct. 22, 1918: 18.

Pennell, J. H. “Field Reports – Zanesville,Oh.” Christian Leader vol. 32 no. 50 Dec. 10, 1918:12.

Poynter, D. J. “Should The Churches Be Closed?” Christian Leader vol. 32 no. 45 Nov. 5, 1918:1.

Rowe, Fred. “Certainly Go To Meeting,” Christian Leader vol. 32 no. 44 Oct. 29, 1918:5.

“Spanish Flu,” Center for Disease Control website, accessed 3-17-2020.